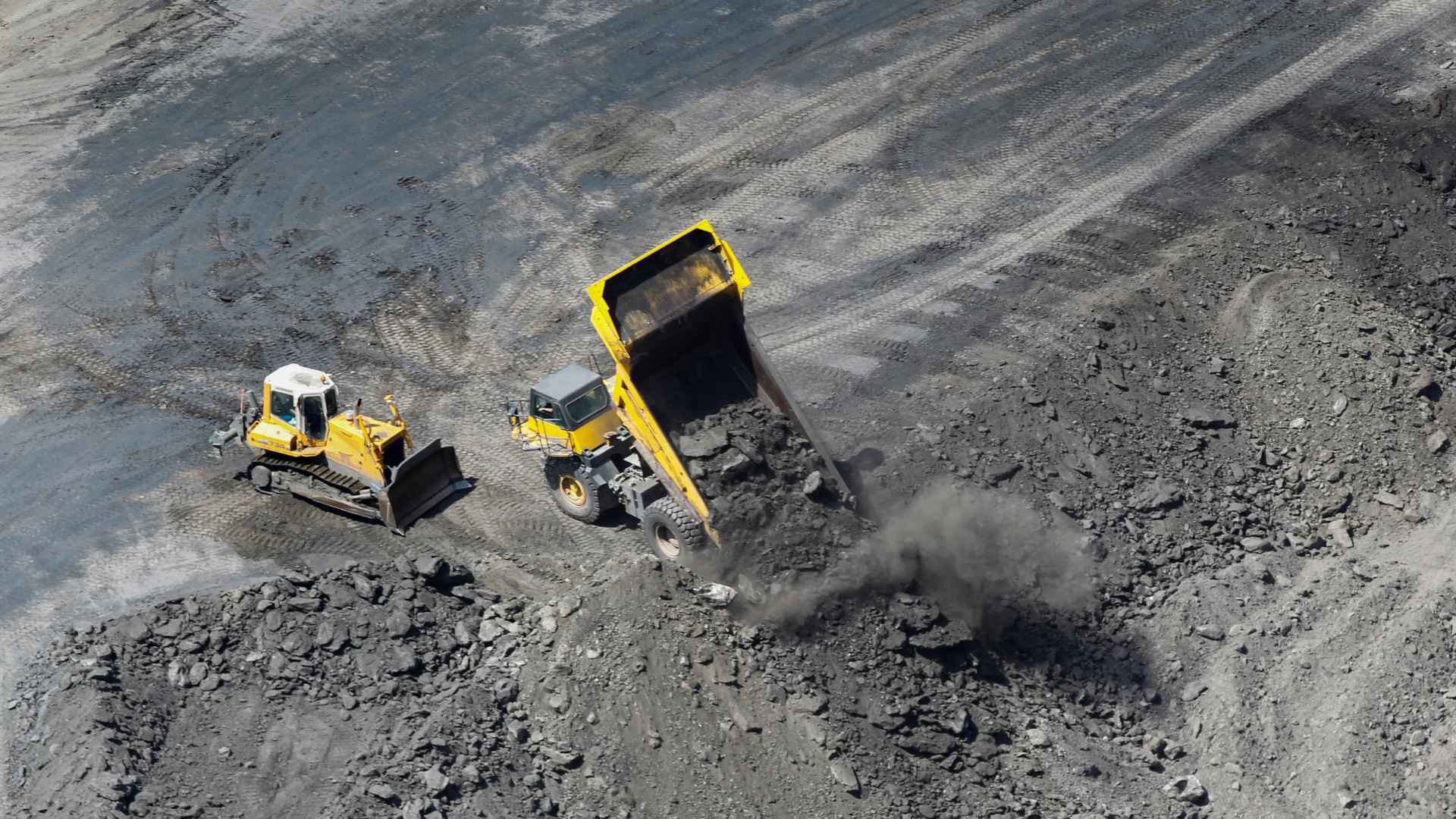

Last week, the Financial Times reported that Coal India Limited (CIL), the world’s largest coal-producing company, will be reopening defunct coal mines to meet India’s growing energy demand. These mines, previously shut down for being uneconomical, will be brought back on line to increase domestic coal production and reduce imports. CIL chair PM Prasad emphasized that coal’s share in India’s energy mix will be maintained until renewable generation and battery storage technologies mature sufficiently to reduce dependence on coal. Unfortunately, this approach will lock India into carbon-intensive infrastructure for decades, complicating the nation’s climate commitments and transition to cleaner energy.

Last week, the Financial Times reported that Coal India Limited (CIL), the world’s largest coal-producing company, will be reopening defunct coal mines to meet India’s growing energy demand. These mines, previously shut down for being uneconomical, will be brought back on line to increase domestic coal production and reduce imports. CIL chair PM Prasad emphasized that coal’s share in India’s energy mix will be maintained until renewable generation and battery storage technologies mature sufficiently to reduce dependence on coal. Unfortunately, this approach will lock India into carbon-intensive infrastructure for decades, complicating the nation’s climate commitments and transition to cleaner energy.

CIL announced its plan to reopen 32 defunct coal mines as early as December last year. At least six mines are expected to start production in fiscal 2025-26. The revival will be managed through revenue-sharing models with private local partners, incentivizing private investment and operational efficiency without heavy upfront government expenditure. CIL has awarded 23 abandoned underground mines to private operators under similar revenue-sharing terms, with contracts lasting up to 25 years and minimum revenue shares set at 4 percent. These mines hold significant extractable reserves, estimated at 635 million tonnes, which could substantially augment domestic coal supply.

Complementing the mine reopening initiative are several policy reforms aimed at promoting coal production and private sector participation. The Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Amendment Act, 2021, permits captive mine owners to sell up to 50% of their coal in the open market, increasing coal availability. Additionally, the 2020 commercial mining auction scheme offers liberal terms including no restrictions on coal use and 100% FDI through the automatic route. The Ministry of Coal provides incentives for underground mining such as reduced revenue share and waived upfront payments to enhance financial viability and sustainability.

The coal expansion strategy risks locking India into carbon-intensive infrastructure, creating fixed costs that hinder renewable energy investments. It would increase greenhouse gas emissions, including potent methane from reopened mines, while diverting focus from essential mine closure and environmental restoration needed for a just transition. Additionally, mechanization reduces coal mining jobs, complicating efforts to reskill workers for the renewable energy sector.

India’s heavy reliance on coal reveals a significant gap in renewable capacity and storage despite adding 25 GW of renewables in 2024, reaching 217.62 GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by January 2025. However, this growth is insufficient to meet the 500 GW target by 2030, with clean energy investments at $13.3 billion in 2024—only one-sixth of the $68 billion required annually. Structural challenges like regulatory hurdles and inadequate grid infrastructure risk a 100 GW shortfall by 2030, while coal still generated 74% of electricity in 2024, underscoring the urgent need to accelerate the energy transition.

Critical questions arise about India’s renewable energy strategy over the past 15 years and why it has not led to a more substantial reduction in coal reliance. The gap between ambitious targets and actual deployment suggests that while policy frameworks and targets have been established, execution bottlenecks and investment shortfalls have slowed progress. Addressing these systemic issues is essential if India is to transition away from coal and meet its climate and clean energy commitments by 2030.

Reopening defunct coal mines risks increasing greenhouse gas emissions, especially methane, which undermines India’s short-term climate goals. Long-term contracts of up to 25 years could lock India into coal dependency beyond its 2035 peak production target and 2070 net-zero commitment. This strategy risks crowding out renewable investments by creating fixed costs and long-term coal purchase obligations, hindering the transition to a low-carbon energy system.

In conclusion, as the world phases out coal to combat the climate crisis, India must commit to no new coal projects and set a clear timeline to retire existing plants. Reintroducing coal would delay the energy transition and hinder renewable investments. Renewables offer affordable, secure electricity, free from price volatility and geopolitical risks. Moreover, the overall costs of burning coal exceed those of replacing it with renewable energy, underscoring the economic and environmental imperative for India to accelerate its shift to clean power.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram and WhatsApp. Click here to join our Telegram channel and click here to join our WhatsApp channel and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.