In effect, India’s tax system mimics advanced economies in numbers but lacks the redistributive structure of the progressive nations. The World Economic Forum (WEF) has described severe income inequality as the biggest risk facing the world. Credit: IPS

The World Economic Forum (WEF) has described severe income inequality as the biggest risk facing the world. Credit: IPS

“Tax terrorism” – that’s how the opposition described the government’s growing dependence on personal income tax (PIT) from the salaried middle class earlier this year. While the phrase may sound a bit provocative, it points to a deeper structural change. For the first time since Independence, PIT collections have overtaken corporate income tax (CIT). This isn’t just a one-time statistical anomaly, but marks a long-term shift where the tax burden is moving from corporate profits to individual salaries and the poorer strata.

In 2023-24, PIT made up a larger share of direct tax revenue than CIT. More importantly, PIT is growing much faster than CIT when measured against GDP growth (tax buoyancy). While middle-income earners are paying more in taxes, corporate profits and personal wealth of the rich continue to benefit from relatively light taxation through lower rates, exemptions and incentives.

Over the last decade, India’s tax regime has tilted in favour of corporates and indirect taxes. Corporate tax rates fell from 30% to 22% for domestic firms and to 15% for new manufacturers, yet collections declined from 3.5% to 2.8% of the GDP. Meanwhile, the GST revenue more than doubled from Rs 4.4 lakh crore to Rs 22.08 lakh crore in the last 5 years, with year-on-year growth of 9.4%.

These consumption-based taxes are regressive, levied uniformly regardless of income, and strike hardest on lower- and middle-income households who cannot shield income or shift liabilities. The combined weight of PIT and GST reveals a tax system that extracts more from those with less.

This has resulted in household savings falling from over 20% to 18.1% of the GDP; net financial savings dropping to a 47-year low low of 5.1%; and household debt surging to 41.9% of GDP. The RBI has raised concerns that this debt is increasingly funding consumption needs (daily needs, groceries, fees, and medical bills rather than creating assets for future needs.

Such a skewed taxation regime has served to worsen inequality. The World Bank’s “ India Poverty and Equity Brief”, 2025, mentions that while the extreme poverty dropped to 2.3%, income inequality worsened. India’s income Gini rose from 52 to 62, highlighting how growth and taxation continue to benefit the top few more than the rest. It affirms that despite poverty reduction, rising income inequality and financial stress show a system skewed against the vulnerable sections. In 2023-24, listed company profits rose 22.3%, but employment grew just 1.5%. The top 10% earned 13 times more than the bottom 10%.

India’s taxation trajectory thus resembles OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) economies which also collect more from individuals than from corporations. Does that mean we are in sync with their trajectory? There are two caveats that need to be inserted here.

First, aligning with OECD countries is not a sure shot sign of comprehensive well being as some of those nations, such as those in Latin America, the United States and Turkey, show high inequality and minuscule social spending. Second, many OECD countries, such as the Nordic nations, often balance their taxation regimes with wealth taxes on the rich, social protection, greater redistribution, stronger social spending and progressive tax structure.

India’s present shift, with high taxes on personal incomes of middle classes and indirect taxes on the poor, mirrors those OECD countries which boast of high inequality and shrinking social expenditures. At the same time, we lack safeguards and social protections which exist in more welfare-driven OECD countries.

How the Tax Burden has Shifted?

For the first time, PIT collections have surpassed CIT in 2023–24, with PIT contributing Rs 10.45 lakh crore versus Rs 9.11 lakh crore from CIT.

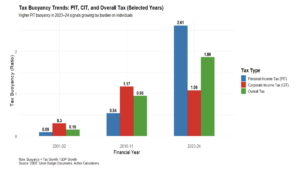

This shift is reinforced by tax buoyancy (the responsiveness of tax revenue to GDP growth). PIT’s buoyancy i.e., its growth relative to GDP, was 2.61, far outpacing CIT’s 1.08. Over two decades, PIT buoyancy rose from 0.09 (2001–02) to 2.61, while CIT’s declined to nearly 1.

This divergence highlights a tax system increasingly reliant on individual incomes, while corporate profits continue to benefit from concessions and lower effective tax rates stark disparity has emerged in corporate India. According to a State Bank of India analysis, 4,000 listed companies recorded only 6% revenue growth, while employee expenses rose just 13%, down from 17% in FY23. This underscores a clear focus on cost-cutting over workforce expansion, as flagged in this year’s Economic Survey. This divergence – soaring profits alongside stagnant employment and wage growth – raises concerns about an economic model increasingly skewed in favour of capital.

Policy-driven incentives like the corporate tax cut (from 30% to 22%, or 15% for new manufacturing), Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes, and start-up exemptions have further boosted margins. Yet, there has been no commensurate sharing of gains with workers either through taxes or wages.

Who Are the Taxpayers?

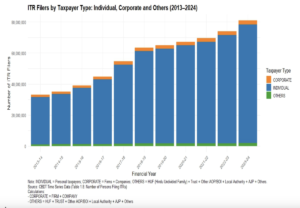

While a broader income tax base signals that more people are paying taxes and the tax structure is maturing, it also raises concerns about equity. Over 90% of ITRs are filed by salaried, middle-income earners, with TDS limiting scope for tax planning. In contrast, high-income groups and corporates, despite benefiting from falling effective tax rates, form a small share of tax filers.

From 2013–14 to 2023–24, individual ITRs more than doubled (3 crore to 7.6 crore), while corporate filings remained flat. While the salaried middle class should rightly contribute to nation-building through their taxes, the concern lies in the increasingly skewed distribution of the tax burden wherein the super-rich are being spared of their share in taxes.

SBI research shows those earning over Rs 10 crore contributed just 2.28% of PIT in 2020–21 (down from 2.81%), and the contributions Rs 100 crore+ earners dropped from 1.64% to 0.77%. Meanwhile, the Rs 5–25 lakh salaried group tripled in filings. India’s tax base is now “narrow at the top and deep in the middle.”

Is India mirroring the trend in advanced capitalist countries?

India’s growing dependence on personal income tax (PIT) and indirect taxes may resemble trends in advanced capitalist economies, but the similarities end there. In OECD countries, PIT contributes around 8% of GDP. In India, it’s less than half of that at 3.5%. What’s more, in several OECD nations, PIT is drawn from a wide base and supports rights-based universal welfare. In India, rising PIT is mainly from the salaried middle class, while corporate tax collections have declined due to repeated policy concessions.

At the same time, India’s indirect tax reliance has surged to around 45% of total tax revenue that comes majorly from consumption taxes like GST, compared to the OECD average of 30–35%. Yet, unlike several OECD counterparts that offer universal public services as a right, India provides only limited and targeted schemes. Countries like the UK, Germany, and France provide free or low-cost healthcare, education, pensions and childcare, funded by taxes. In contrast, India’s schemes like Ayushman Bharat or PM Ujjwala are targeted, often exclusionary, and many (like Ayushman Bharat) rely on private service providers, pushing households to pay out of pocket.

This creates a double burden: the salaried middle class pays more in income tax and GST, yet still has to spend on private healthcare, education and retirement. As a result, their ability to save or invest in assets is steadily shrinking. RBI’s financial stability report shows that over 55% of household debt is now used for consumption needs (credit cards, personal expenses), while housing and productive assets make up for just 29%. This lack of social protection not only increases financial strain on the middle class but also on the poorer section through indirect taxes, deepening economic inequality.

Compounding this, India has eliminated or diluted key redistributive tools. The wealth tax was abolished in 2015, capital income enjoys favourable tax treatment, and there is no inheritance tax. This reinforces inequality. Meanwhile, the top 1% own over 40% of national wealth; the bottom 50% hold just 3%. Even OECD nations, where the top 10% own 52% of wealth, maintain estate taxes (up to 55% in Japan) to moderate inequality. Meanwhile, many OECD countries also impose significant inheritance or estate taxes on large estates, such as France (up to 45%), Germany (up to 50%), and Japan (up to 55%)

In 2022, OECD countries spent an average of 21% of GDP on public social services. Top spenders like France, Finland, and Denmark allocated over 30%, while Sweden, Norway, Germany, and Austria spent between 25-30%. India, in contrast, spent just 1.9% on health and 2.7% on education in 2021-22, with total social sector spending at only 7.6% of GDP, as per the Economic Survey 2024-25.

A parliamentary committee also flagged that India’s education spending is not only below global standards but even trails SAARC neighbours like Bhutan and the Maldives. This means Indian taxpayers, especially the middle class and those in the lower strata, must self-finance healthcare, education and retirement despite paying significant taxes.

In effect, India’s tax system mimics advanced economies in numbers but lacks the redistributive structure of the more progressive ones. What we are witnessing is a move reinforcing neoliberal capitalism with regressive taxation, where the poor and the middle class pays more and gets less.

India needs tax reform not only for efficiency but for fairness. This includes a progressive wealth tax and inheritance tax on the ultra-rich, closing loopholes that favour the top 1%, and aligning taxes on capital income with those on salaries. Simultaneously, GST on essential goods must be reduced or eliminated to relieve the poor and working class, for whom consumption taxes hit the hardest.

These reforms are not merely policy suggestions; but they are in line with constitutional mandates. The preamble promises economic justice, and Article 38 under Directive Principles for State Policy directs the state to reduce income and wealth inequalities. Adding to this, the Supreme Court, in D.S. Nakara vs Union of India, affirmed that redistribution is integral to India’s constitutional vision. A fairer tax system is essential to uphold that promise.

This article was originally published in The Wire and you can read here.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram and WhatsApp. Click here to join our Telegram channel and click here to join our WhatsApp channel, and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.