Modern aesthetics and digital technology are no indication of how inclusive, walkable, breathable, and democratic a city truly is.

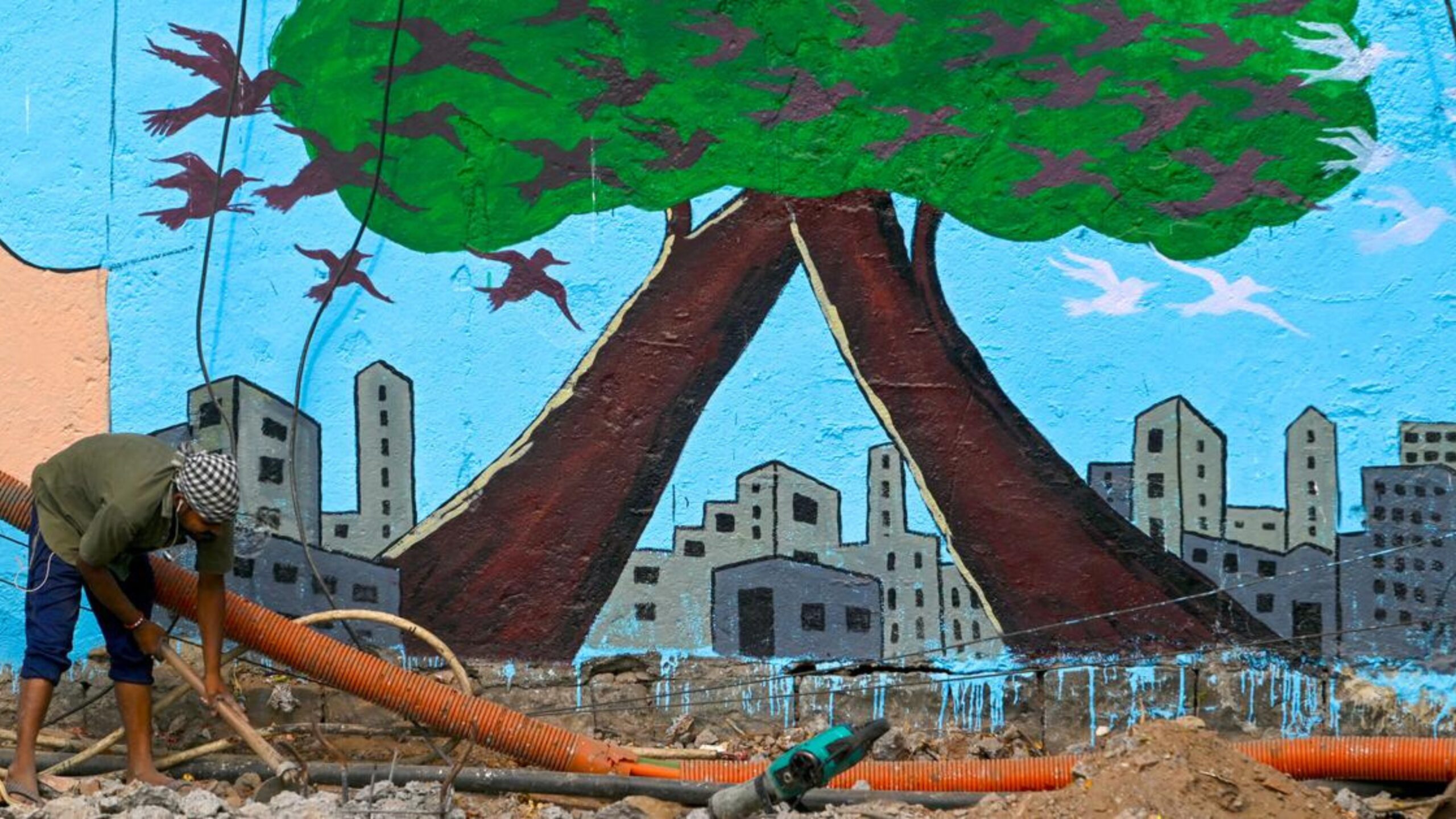

A labourer digs a portion of a footpath as part of a beautification project in Mumbai on March 23, 2022. (Photo by Indranil MUKHERJEE / AFP) | AFP

When the Smart Cities Mission was launched by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2015, it promised to transform urban India into a network of high-tech, citizen-friendly spaces.

It came riding on the language of innovation, sustainability, and modern governance, powered by the Internet of Things – a network of devices that share data. On paper, it seemed like a visionary leap into the future. But a decade later, the glimmer has dimmed. Beneath the surface of command centres, digital kiosks and sensor-laden poles lies a deeper story of displacement, ecological degradation and the steady erosion of the urban commons.

Infrastructure trumps inclusion

The “smart city” became synonymous not with inclusive planning but with an obsession for capital-intensive infrastructure, often designed without regard for the lived experiences of people.

It was driven by a narrow technocratic impulse, not ecological wisdom or community consultation. In city after city, footpaths, parks, lakes, and playgrounds – spaces that once formed the fabric of urban life – were appropriated, neglected, or destroyed in the name of smart redevelopment.

Vanishing footpaths

Take Bengaluru, one of the pilot cities of the mission. Under the Smart City plan, the city saw the rapid construction of flyovers and signal-free corridors. While these projects boasted that they had eased vehicular movement, they quietly gobbled up footpaths or made them inaccessible. In Miller’s Road, newly laid pedestrian paths were soon buried under construction debris. Citizens reported trench digging in the middle of the night that rendered entire stretches unusable for weeks.

Even Cubbon Park, the city’s historic green lung, was not spared. A Smart City-funded proposal to build a sensory park within it sparked widespread outrage as it threatened to intrude into ecologically sensitive zones.

This was not an isolated story. In Bhopal, another smart city, pedestrian walkways were either broken, blocked by vendors, or simply non-existent. The same story played out in Ranchi, where motorbikes and cars routinely parked on sidewalks, pushing pedestrians onto busy roads.

Instead of creating walkable cities, the ground reality remained dangerously hostile to walkers. Footpaths were treated not as integral civic assets but as flexible territories to be reconfigured for other priorities.

Ecological neglect

Lakes, wetlands, and urban parks – long-standing ecological and social assets – also became collateral damage in the high-stakes redevelopment game. In Coimbatore, seven historic lakes were revitalised under the Smart City budget with promenades, fountains, and viewing decks. Yet, within a year, many turned into garbage-strewn, mosquito-infested stretches. Locals complained about poor maintenance, broken benches, and unhygienic public toilets.

The lakes, once community spaces, became fenced-off, semi-privatised zones catering more to aesthetics than function.

In Kolkata, the development of Rajarhat or New Town, framed as a smart satellite city, systematically erased wetlands and ponds that once defined the peri-urban ecology of the area. Water bodies were filled and paved to make way for luxury housing and tech parks. What was marketed as a climate-resilient township turned out to be a textbook example of ecological amnesia.

Similarly, in Guwahati, marginal wetlands such as Sola Beel were encroached upon, displacing not just water systems but also the poorer communities dependent on them for livelihood.

Grey zones, lost potential

Meanwhile, the grey zones of infrastructure – spaces under flyovers and overpasses – were left degraded or converted into commercial enclaves. In Ahmedabad, these under-flyover areas were initially envisioned as vibrant commons, featuring libraries, markets, and shaded seating. But implementation lagged, and many turned into dumping grounds or informal parking lots.

Bengaluru, again, witnessed a similar situation until civil society groups like The Ugly Indian stepped in to reclaim these dead zones with colour, cleanliness, and community participation.

Slum redevelopment, another pillar under smart city projects, became a convenient excuse for the dispossession of the poor. In Ahmedabad, slum clusters such as Ramo Tekri were marked for Smart City redevelopment without proper surveys or community involvement. Displaced residents lamented the loss of their community spaces, informal parks, and water access points.

In Pune and Bhubaneswar, affordable housing under Smart City plans replaced informal settlements with rigid high-rises, severing social and ecological networks that had organically evolved over decades.

Ecology ignored

What emerges across these examples is a pattern of systemic disregard for ecological planning. The Smart Cities Mission privileged hard infrastructure – concrete roads, command centers, surveillance cameras – over environmental resilience.

Urban lakes were beautified, not restored. Parks were branded with Wi-Fi and LED signage while lacking shade and sanitation. The technological sheen concealed the hollowness beneath. Smart streets emerged without drainage planning. Footpaths were laid without ensuring connectivity or accessibility. Riverfronts were built while upstream wetlands were choked. The ecological web was consistently broken by linear, capital-intensive interventions.

Citizen pushback

In several cities, protests erupted over the misuse of the commons. In Bengaluru, residents campaigned against the privatisation of Hebbal Lake. In Jaipur, the Supreme Court criticisied the authorities for polluting the Jal Mahal Lake even as they sought smart city accolades.

Environmental groups in Navi Mumbai raised alarms when DPS Lake, a birding haven, faced water blockades due to surrounding construction.

In each case, the Smart City apparatus appeared more eager to chase metrics than uphold sustainability.

Technology without context

Even more worrying was the blind faith in technology. Cities poured crores into Integrated Command and Control Centres, traffic sensors and surveillance grids. Yet, basic issues like clean air, functional drainage, and safe pedestrian mobility remained unresolved.

“You can have an app that tells you when the next bus will arrive,” one citizen observed. “But what use is that if there’s no bus stop, or worse, no sidewalk to get to it?”

Furthermore, there is a lack of integration within these control centres. Most of the centres are controlled either by the police or district authorities, the city governance structure being a mere spectator.

Call to reclaim the city

The Smart City Mission, in its present avatar, reflects a deeper malaise in Indian urbanism: a desire to appear modern without truly engaging with the social and ecological complexities of cities.

The commons – those messy, vibrant, shared spaces that resist commodification –were always inconvenient to the smart city imagination. They could not be easily surveilled, monetised, or standardised. So, they were erased, fenced, or rebranded until their original character disappeared.

Yet, the future need not be a continuation of this erasure. As cities reckon with climate change, social inequity and declining public trust, there is a growing realisation that smartness must be redefined – not by the number of sensors or square footage of smart roads, but by how inclusive, walkable, breathable and democratic a city truly is.

It’s time to move beyond the spectacle of smart cities and reclaim the city itself – not as a grid of sensors but as a living commons. Only then can urban India become not just smart, but wise.

Tikender Singh Panwar is an urban policy expert and former Deputy Mayor of Shimla, known for his work on inclusive and sustainable city governance. Author of three books-” Cities in Transition’, “The Radical City”, and “Challenges of Urban Governance”

This article is the first in a series on 10 years of the Smart Cities Mission, curated for Scroll by the Centre for Financial Accountability. It was originally published in Scroll, and you can read here.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram and WhatsApp. Click here to join our Telegram channel and click here to join our WhatsApp channel, and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.