The Smart Cities Project, since its introduction in India, has garnered both applause and criticism and despite the mixed response, has successfully rewired the very imagination of the Indian city. This article attempts to throw light on implementation of Smart Cities Mission in India, and how it transforms and mutates the existing governance structures and progressive policies with the help of relevant case studies and narratives from the ground.

This budget season, like a slew of promises made five years ago, the BJP led NDA government has little to say on the Smart Cities. The program came as part of Modi’s onslaught on the public imagination and as a continuation of the ‘Gujrat Model’ of development, instrumental in securing BJP a simple majority after three decades in 2014. At the onset of the program, it was quite unclear what these Smart Cities would be. The rhetoric employed to articulate this new kind of urban development seemed progressive and purposive. The 2014 BJP manifesto highlighted that – “our cities should no longer remain a reflection of poverty and bottlenecks. Rather they should become symbols of efficiency, speed and scale” (emphasis added).[1] And that the new government will “initiate building 100 new cities; enabled with the latest in technology and infrastructure – adhering to concepts like sustainability, walk to work etc., and focused on specialized domains.” However vague it sounded, the imagined smart city worked wonders with the masses and catapulted the narrative of 100 new (smart) cities into public perception.

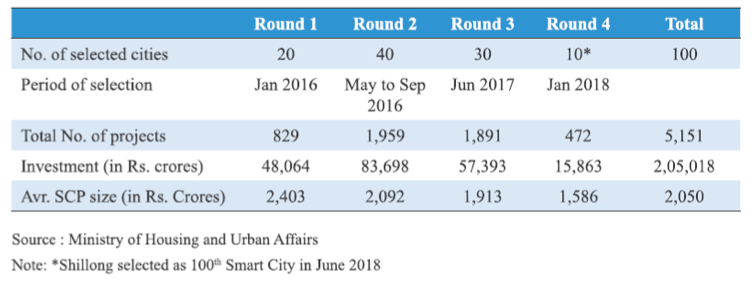

By 2015, the idea had metamorphosed and had achieved a more plausible, actionable form, if not an articulate one. The smart city was defined as “one having provision of basic infrastructure to give a decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of smart solutions, keeping the citizens at the centre.”[2] As per Smart Cities Mission guidelines, the Central government had proposed financial support to the extent of ₹48,000 crore (23.4 per cent of Smart City Proposal value) over five years, i.e. an average of ₹500 crore per city. An equal amount, on a matching basis, is provided by the State/Urban Local Body (ULB). Apart from these, being very ambitious, around ₹42,028 crore (21 per cent) is expected from convergence with other Missions, ₹41,022 crore (20 per cent) from Public Private Partnerships (PPP), around ₹9,843 crore (4.8 per cent) from loans, ₹2,644 crore (1.3 per cent) from own resources and rest from other sources.[3]

The mission guidelines acknowledge there is “no universally accepted definition” of a smart city. But the mission objective is described as promoting “cities that provide core infrastructure and give a decent quality of life to its citizens, a clean and sustainable environment and application of ‘Smart’ Solutions.” It also imagined “driving economic growth and improve the quality of life of people by enabling local area development and harnessing technology, especially technology that leads to Smart outcomes.” The mission also adopted a two-pronged strategy for the same. Firstly, Area Based Development that – “will transform existing areas (retrofit and redevelop), including slums, into better-planned ones, thereby improving liveability of the whole City.” Secondly, a more technology-centric solution which “will enable cities to use technology, information and data to improve infrastructure and services. Comprehensive development in this way will improve quality of life, create employment and enhance incomes for all, especially the poor and the disadvantaged, leading to inclusive Cities.” [4]

Figure 1: Expected source of funding under Smart City Mission. Source: Economic Survey of India, Volume II, 2019.

The last four years of the SCM implementation has been usually dubious, fragmented and at best chequered. Divorced from people’s lived realities and their needs, Smart Cities ended up packaging the ‘development’ rhetoric, which though infused with apt sounding words, left a lot desired in terms of detailed planning and execution. The attractive and catchy wording of the Smarty City has meant that it has led India’s urbanisation discourse with a departure from all previous models and methods. And will continue to do so. The concept of the Smart City, in the Indian context, is vague enough to transcend regional and local variations, loose enough as an instrument to allow cities to be viewed as “more competitive”. The lack of fixed meaning, with the usage of buzzwords like inclusivity and sustainability in the SCM, meant it could be communicated as a pro-people, reformative scheme. Into the first two years of implementation, it was increasingly clear that Smart City Mission was inherently unsmart.[5]It has been now studied that the project is nor IT solution–centric, nor is it people-centric. Public participation that should form the foundations of any urban development intervention is absent; If present, merely tokenistic. Participation was in many cases encouraged in the form twitter RTs, and Facebook likes, leaving out a vast majority of possible scheme affected citizens. It was also apparent that the project – leave alone the new cities – has been drastically reduced to the scale of elite enclaves in our vastly impoverished cities. On average, the ABD (Area Based Development) proposals and projects corner up to 80% of the funds but are concentrated only on 5 – 10% of the city area.[6] It is thereby deepening inequalities within the city. It has been noticed that to keep up to the unrealistic standards and benchmarks to be achieved in the competitive mode of SCM, the ABDs are usually the more developed areas of the city. Thereby further diluting the purpose of a mission to improve the conditions of a city holistically.

| Financial Year | Approved | Allocation | Released |

| 2015-16 | 4,000 | 1,496.20 | 1,469.20 |

| 2016-17 | 10,000 | 4,598.50 | 4,492.50 |

| 2017-18 | 14,000 | 4,509.50 | 4,499.50 |

| 2018-19 | 10,000 | 6,000.00 | 5,856.80 |

| 2019-20 | 10,000 | 6,450.00 | 796.00 |

| Total | 48,000 Cr | 23,054.20 Cr | 17,114.00 Cr |

Table 2: The details of SCM funds approved, budgetary allocations and releases under the Mission

Beyond the structural concerns of the smart cities mission as a design, the other focus has been on the increasing evictions and displacements induced by SCM.[7] Numerous such instances have been recorded in the studies, pointing at the roadblocks encountered in the implementation of the scheme. Thereby signalling the aloofness from hard realities. Of all the schemes by the Modi led government, smart cities have faced stiff challenges on the ground. Till July 2019, of the promised 48,000 Cr, only 17114 Cr has been released by the Central Government and only 6160 Cr has been utilized by the cities – a mere 3% of the total estimated costs of the projects as conceived in 2015. [8]

The underutilisation of funds is also evident from the fact that on comparing expenditure incurred to the funds sanctioned, out of the 35 states/UTs, 26 states have utilised less than 20% of the funds released.[9] Though the fund utilisation seems grim, around it is claimed that 33% of projects (perhaps smaller ones) are under implementation or completed. Also, the mission has now incorporated in all 100 cities Special Purpose Vehicles (SPVs), City Level Advisory Forums (CLAFs) and appointed Project Management Consultants (PMCs); wanting to demonstrate long term sustainability of the initiative. [10] But overall, the efficiency, speed and scale that were promised in 2014 have been missing.

Fast forward to 2019, after very sluggish four years of SCM, the BJP manifesto drops the promise of smart cities in a vastly reduced focus on urban development; unlike the 2014 manifesto.[11] The reduced urban focus has not come in as a surprise to many as there are few numbers and visible developments under the SCM in our cities. The cities have struggled to raise resources. Projects executed were mostly state funded. And the entire program itself was going against the grain of socio-political discourse on development, governance and participation; coupled with an ever increasing resistance by people’s groups. This had launched a debate; a false narrative of the SCM just being another ‘project’ that will be discontinued. This was again reinforced in the non-mention of Smart Cities in 2019 Budget Speech.[12] It is in this context, it is essential to step back and assess the SCM through case narratives, and attempt to understand how it has inalterably impacted the urban development policy programs. Possibly for a long time to come. Unlike the popular idea, as being a relatively unsuccessful program that will recede as quick as it was introduced, I posit, it has given the state a repertoire of means and methods to manage urbanization, irrespective of whether SCM as a program exists or not. Below are the key reasons and means by which SCM will far outlive its four years of the implementation, and is an imagination to stay.

-

Legitimization of Special Purpose Vehicles (SPV) as a governance model

The Smart Cities Mission mandates that each city creates a Special Purpose Vehicle under the Companies Act 2013, which is a limited company which will manage the implementation of the projects under the Mission. This SPV plans, appraises, approves and releases funds to implement further, manage, operate, monitor and evaluate the smart city developmental projects in the concerned city. [13] This is made possible under the alibi of ensuring implementation of the program as the existing urban local governments (ULGs) are without know-how and resources. SPVs, therefore, are being transferred with enormous powers under the SCM, which were originally (constitutionally) the ‘rights and obligations’ of the local municipality.[14] Seemingly harmless, and even described as helpful for the urban local governments, the SPVs are in direct contradiction to the 74th Constitutional Amendment Act that devolves functions of planning and taxation to ULGs. The ambiguous relationship between the elected body and SPV further complicates matters, with usually SPVs run by representatives from the State level running the show. This is in direct contradiction to the objective of the SCM that aims at “empowering local governments”.

Apart from re-centralizing the urban governance that existed, SPVs are also an indication of how the urban futures will be shaped not through citizen/ resident’s democratic engagement but individuals or unelected entities vested with powers. The chief executive officer (CEO) of SPV, usually a senior bureaucrat appointed by the state government has a fixed tenure and cannot be changed without the authorisation of the government of India.[15] Other than this SCM have provisions of bringing in the private sector to be a stakeholder, partner to manage and develop Indian cities. The structure would ordinarily appear to be influenced by industrial township authorities (enshrined in the municipal law but without any elected members) and SPV based governance structures in private townships as promoted by several state governments to promote private sector investment. Though this has not yet really manifested on the ground, as SPVs are still mostly government owned, but with increased investments, this might change.

The SPVs and corporate governance mechanisms have also meant that public engagement and participation has been curtailed. And if at all any public interaction has been carried out it has been exclusionary. Ironically, SCM that claim for transparency and accountability are perpetuating exclusionary models of decision making and non-transparency in the execution of projects and its finances. The SPV model of urban governance introduced under the Smart Cities Mission highlights the nature of the short-sightedness of policymakers, reflecting the false notion that extra-constitutional bodies can address structural challenges associated with urban governance in Indian cities. This as opposed to consistent, long-term processes towards institutional transformation. SPVs, have now become a modus operandi, not limited to big urban centres, but reached the small-town cities that will employ it unscrupulously to thwart decentralization of powers and for all ensuing urban development initiatives at the local level.

-

Urban land monetization as a strategy

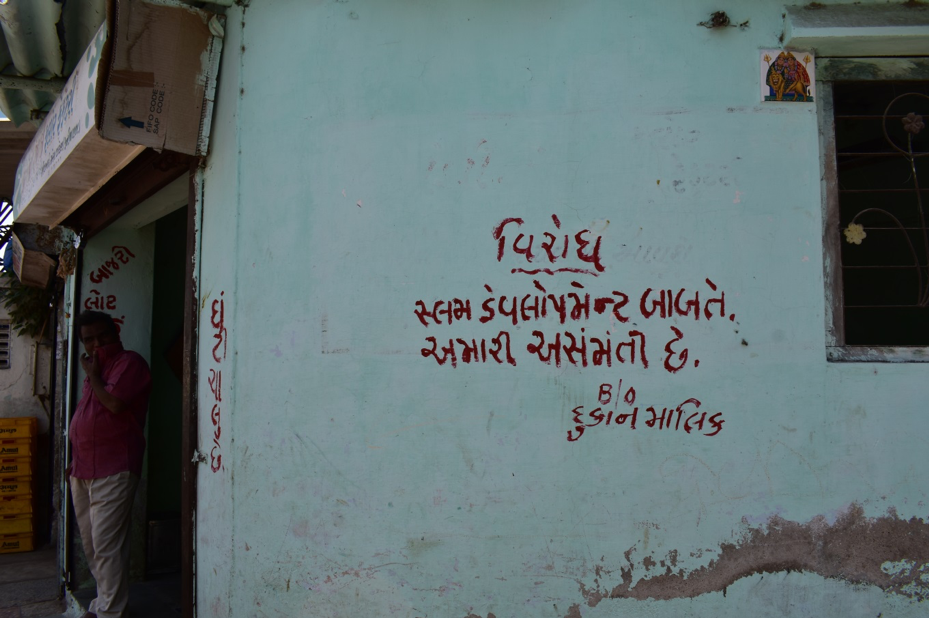

Land under informal settlements or slums, as they are pejoratively called – has always been considered by the state to be sub-optimally used. Housing around 20 – 30% of the urban population, slums can be alternatively seen as people’s response to the housing needs.[16] Aside, from the housing, informal settlements are also a lively hub for a host of informal activities and livelihoods that otherwise find it difficult to be accommodated in the formal market systems. Considering that more than 70% of the workforce in urban India, is employed in the informal sector, slums play a crucial role in harbouring the livelihood needs of our urban areas. The approach to slums over the years, starting from the early 60s to the 1990s has shifted from that of eviction to accommodation, to upgradation and finally a process of slum redevelopment, based on the monetization of land. By 1990s, land had become very lucrative in large urban centres, like Mumbai. It is based on this premise that in 1995, Mumbai established the Slum Rehabilitation Authority that will give free houses to slum dwellers using cross-subsidization as a fiscal tool by monetizing the land value, by selling hi-end apartments in the free-sale component in the market.[17] This scheme, since then, in spite of failings and trenchant critique, has been replicated in phases across the cities of Maharashtra and then later in Gujarat. It was in 2014 that the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojna (PMAY) – Urban adopted one of its four main verticals as an in situ-slum redevelopment.[18] And Smart Cities, along with the PMAY – Urban played a major role in the propagation of in situ-slum redevelopment as a model to be replicated across the numerous cities. This land monetization of informal settlements, now not limited to big cities has put in danger the premise of planning itself – that of social and economic upliftment. Even in smaller cities, where land is not scarce, settlements are relatively not congested, and with ample space for social infrastructure development, the state under the guise of SCM is pushing for the redevelopment of strategic land parcels under informal settlements.

“I am a daily wage labourer. I do not have any understanding of the Smart City Program. Some say it will be beneficial for us, some in our community say that it will be bad for us. We are confused. Six months ago, I was living in my home in Ramo Tekri. The authorities asked us to move to rent. They gave Rs 1 lakh cheque, said that we will get our new home in some time and now are struggling to pay. ”

– Amita Ben, Resident, Ramo Tekri, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

“I have been staying here for more than 25 years. We don’t really know the meaning of the smart city. We are getting small – small houses in the smart city mission, how we will manage our full family. There was no proper survey of the place, only 50% of the residents are eligible to get a house”

– Kamlesh, Resident, Ramo Tekri, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

Image 1: “Virodh” – Opposition to the slum redevelopment in Ahmedabad, Gujarat under Smart City Mission

- Usurping river and lakes and rescaling of unsustainable practices

In the many previous programmes and projects for urban development, rivers and lakes that are historically connected to the city development, transport and culture were relatively safe. But especially since the 2000s, the beautification of Indian rivers and water systems in the urban has been a cause for concern. Utilizing the Sabarmati example at the local in various cities, the SCM has provided the opportunity to the cities to ‘open up’ and ‘reclaim’ the river and water bodies. The Sabarmati riverfront project which began as an urban development project is lately being pushed as a paradigm for many rivers in cities of India. This kind of riverfront development essentially changes the ecological and social scape of the river, transforming it into an urban commercial development meant for consumption rather than a natural, social, cultural, ecological landscape.

A cursory glance at the existing river ‘restoration’ ‘improvement’ ‘beautification’ schemes indicates that the discourse revolves mainly around recreational and commercial activities. It is more about real estate than the river. Activities that are promoted on the riverfronts typically include promenades, boat trips, shopping, small shops, restaurants, theme parks, walkways and even parking lots in the encroached river bed.[19] Riverbanks and flood plains have increasingly being viewed as land that is underutilized on which value could be created by reclaiming and not as seasonal ecological systems that needs to be conserved. It is also proven that in the spree for this commercial development of water systems, a network of activities, people, livelihoods and settlements depending on the rivers will be painted as encroachers, and removed. This is typically visible in all major riverfront developments and ignores the fact that communities depending on water systems are the original custodians and de-facto protectors of the common good. And our environmental protectionism restricts the developments to cementing ‘river banks’ and ‘river parks’. All this is also oblivious to the changing climate needs and adaptations required in the Urban. There are at the moment more than 30 such riverfront and lakeside developments proposed under the SCM. [20] What is more disconcerting is that all this is happening when Indian cities are facing the worst forms of urban floods and droughts.

“I am a fisherman. We have been working in this line (livelihood) for years. We are organized in committees, and we have hundreds of men and families working on this. We are not aware of the Smart City plans. But yes, we have heard that they are planning to beautify the cities and make it look good. Let’s hope that the city will progress. Our livelihood is the prime concern for us. We hope that we are included in the plans for the revival of ponds in the city.”

PM Ramdas Sahni, Fisherman, Marine Drive – Station road, Muzaffarpur, Bihar

“I have been staying in Shekhar Nagar for 15 years. We were told that we were made part of the Smart City program. But this was without our consent or our participation. Nothing has changed for us. Under the guise of cleaning river Kahn, they have demolished so many houses and bastis. Yes, we agree that the river must be clean, but who are we cleaning it for, and why demolish houses. Now they are making gardens and open space on it, as a tourist destination and a luxury where people are still fighting for their food and shelter.”

– Sandeep Chandan Singh, Shekhar Nagar, Indore, Madhya Pradesh

- Propagation of un-smart mobility plans

The promise to improve public transportation and road connectivity usually finds mention in all pre-poll declarations — though often only to be forgotten later. There is an overwhelming consensus, over the need for strengthening public transportation and ensuring equitable access to the same, along with safety issues addressed. The SCM, in its project allocation, has favoured the private vehicle user over public transport users and pedestrians. A lot of PAN city proposals have been reduced to traffic monitoring systems, using a high proportion of The IT component at almost 30% under the transportation head of SCM. But even then, the bulk of transportation projects are focused on roads and parking lots (nearly 40%), while only 20% of the budget is focused on public transportation, only 2% of the entire transportation budget is focused on buses.[21]

A particular focus on gender, marginalised sections and people with disabilities is not visible in all the guidelines. Though the emphasis on non-formal, non-motorized transportation modes with special attention to walking and cycling is also reassuring, the Mission focuses only 13% of the budget on non-motorised transportation, and the rest is mostly devoted to supporting motorised transportation systems. Given that one of the purposes of the Smart Cities Mission is enhancing sustainability, this particular project is better suited for owners of private transportation. Moving ahead, it remains to be seen how we can ensure that the debate remains rooted in real public transport options and we do not end up espousing the increase of cars on Indian roads. The need is to strive to measure Indian cities with parameters of walkability and cycling, and more radically by the increased presence of walkable footpaths.

- Dilution of a rights-based approach to planning under the Smart Cities mission

Smart cities and its implementation; though relatively slow as compared to other missions have possibly had a profound impact on the dilution of rights in urban development discourse in India. The numerous mainstream and marginal sections, in spite of robust legal and constitutional provisions, have been unable to engage in the city planning process. The mission stands in contra-distinction to the Master Plans that most of the cities have, that have a legal backing and possibly better statutory spaces for engagement. Smart city planning cannot be parallel to the democratic city planning process and has to be dovetailed to holistic city planning needs; unlike how it is done today. This further has to be decentralized as per the mandate of 74th CAA. Other than this the numerous laws, regulations and policy frameworks that exist to protect slum settlements, street vendors, the homeless populations and pedestrians and so on, have to be included in the mission guidelines to ensure that capital pressures do not disregard the safeguards to marginal groups.

“This area was originally not under the Smart City Mission. After some days, we got to know that the development in Indore focuses on smooth roads, mobility, and so on. We had our houses demolished to make way for wider roads. We were partially compensated, and we lost our ancestral property. They did not even consult us before planning for such drastic measures. The Smart City plan has gone awry for us.”

– Jahid Ali, Karaoghat, Indore, Madhya Pradesh

“I have come to Chennai for livelihood. I am originally from south Tamil Nadu, Dindugal. This has been my profession for the last 25 years. And I have always been selling flowers. This Smart City plan has come in as a rude shock to us. I don’t know much about this. This construction work of footpaths in T Nagar Road has affected the inflow of our customers. While drawing up the plans, they did not meet us or speak to us for our demands. We demand the right to livelihoods as street vendors and seek the Chennai Corporation to allot us permanent space for livelihoods.”

– Shanthi, Pondy Bazaar, T Nagar, Chennai, Tamil Nadu

Image 8: Road widening in Smart City plans leading to the demolition of old housing settlements in Indore, Madhya Pradesh

Conclusion

The Indian variation of the smart city is not a scheme or a project. And its analysis cannot be limited to the analysis of its structure, the expenditures and the failures in the implementation. The Smart City Mission, as is visible in its manifestation in the Indian urban reveals that it has now offered a means, a raison d’etre and a repertoire of urban interventions to the city governments pushed by SPVs through which to ‘develop’ their cities. Development here need not be confused with human or ecological, but essentially economic in nature. The smart cities mission in the country has become a vehicle to transport a neo-liberal paradigm(s) of urbanisation and urban development to cities and towns which were yet to think in terms of urban planning.

While on paper, the SCM may offer frameworks and structures, but within a competitive and time-bound programme, most of the guidelines seem to be ambiguously – flexible and very often overlooked in the name of the greater good, creating aberrations to the very idea of the Smart City. Considering that the Smart City Mission, is a futuristic project, its engagement with increasingly palpable concerns like climate change and environmental degradation is minimal. The language and practice of making equitable and right-based decisions on urban planning and design have also been lost in the process, and the future of the ‘people’ in the smart cities, if continued on the existing lines, looks bleak. The Smart City experience in India has been top-down, gift-wrapped impressively in the name of ‘Development’. Whether or not the Smart City will change its course in the future, one does not know but looks highly unlikely. In hindsight, the SCM is more of an opportunity, that has been lost in creating and promoting local forms of urbanisations for cities and towns which remained outside the realm of mainstream, urban planning and development, and could have discovered urbanisation which is localised, democratic, equitable and functional for people across classes and social groups.

Aravind Unni is an activist and urban researcher, associated with a civil society platform called National Coalition for Inclusive and Sustainable Urbanization. He was also the recipient of the First Smitu Kothari Fellowship. All photographs and interviews are courtesy of Vikas Kumar and Khushwant Singh.

[1] For BJP 2014 Manifesto, please refer – https://www.thehinducentre.com/resources/article5882297.ece

[2] http://smartcities.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/SmartCityGuidelines(1).pdf

[3] https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/specials/india-file/whats-smart-about-smart-cities/article26367835.ece

[4] http://smartcities.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/SmartCityGuidelines(1).pdf

[5] https://www.hindustantimes.com/analysis/many-of-india-s-proposed-smart-city-projects-are-actually-unsmart/story-szejxW8KwZxf03lnkca6QI.html

[6] https://cprindia.org/system/tdf/policy-briefs/SCM%20POLICY%20BRIEF%2028th%20Aug.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=7162

[7] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-landrights-housing idUSKCN11Y04U?utm_medium=website&utm_source=archdaily.com

[8] Ministry Of Housing and Urban Affairs, GOI; RAJYA SABHA, UNSTARRED QUESTION NO-1988, ANSWERED ON-10.07.2019, Current status of Smart City Mission

[9] https://thewire.in/urban/smart-cities-mission-reality

[10] Economic Survey of India, Volume II, 2019 – Please refer https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/economicsurvey/

[11] The concept of smart cities has also been critiqued and has been censured in the election manifestos of other political parties, which in opposition to smart cities have coined liveable cities (in the case of CPIM). Or as in the case of INC, stops short of proposing an alternative to SCM. Please refer – https://cpim.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019-ls-elc-manifesto.pdf & https://manifesto.inc.in/pdf/english.pdf

[12] https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/doc/Budget_Speech.pdf

[13] https://www.epw.in/engage/article/what-do-our-cities-need-become-inclusive-smart-cities

[14] https://www.india.gov.in/my-government/constitution-india/amendments/constitution-india-seventy-fourth-amendment-act-1992

[15] https://www.hindustantimes.com/real-estate/how-will-a-spv-in-a-smart-city-work/story-2zSGIwMztItpzPZA9TuXeM.html

[16] Census pitches the slum population figure to around 17% – please refer http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-Documents/Slum-26-09-13.pdf

[17] Please refer SRA website for more details- https://sra.gov.in/page/innerpage/department-history.php

[18] https://pmaymis.gov.in/PDF/HFA_Guidelines/hfa_Guidelines.pdf

[19] https://sandrp.in/2014/09/17/riverfront-development-in-india-cosmetic-make-up-on-deep-wounds/

[20] https://smartnet.niua.org/sites/default/files/resources/List_of_Projects_OpenSpaces_Riverfront.pdf

[21] https://cprindia.org/system/tdf/policy briefs/SCM%20POLICY%20BRIEF%2028th%20Aug.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=7162