Since the Tata Mundra “Ultra Mega Power Project” broke ground in 2008, many once-fertile fishing and farming communities of Northwest India have been ravaged. Photo by Sami Siva/Redux

WILD ANIMALS ONCE RAN AMONG the acacia trees outside Navinal, one of many small villages hugging the Gulf of Kutch–an inlet on India’s northwest coast. Gajendra Singh Jadeja remembers them well: Cattle foraged for food in the forests and on the grazing land of India’s westernmost state, Gujarat, not far from where villagers in boats dragged in catches of catfish and prawns. Then Adani Power broke ground on the region’s first coal-fired power plant. Soon another followed, and that’s when everything changed.

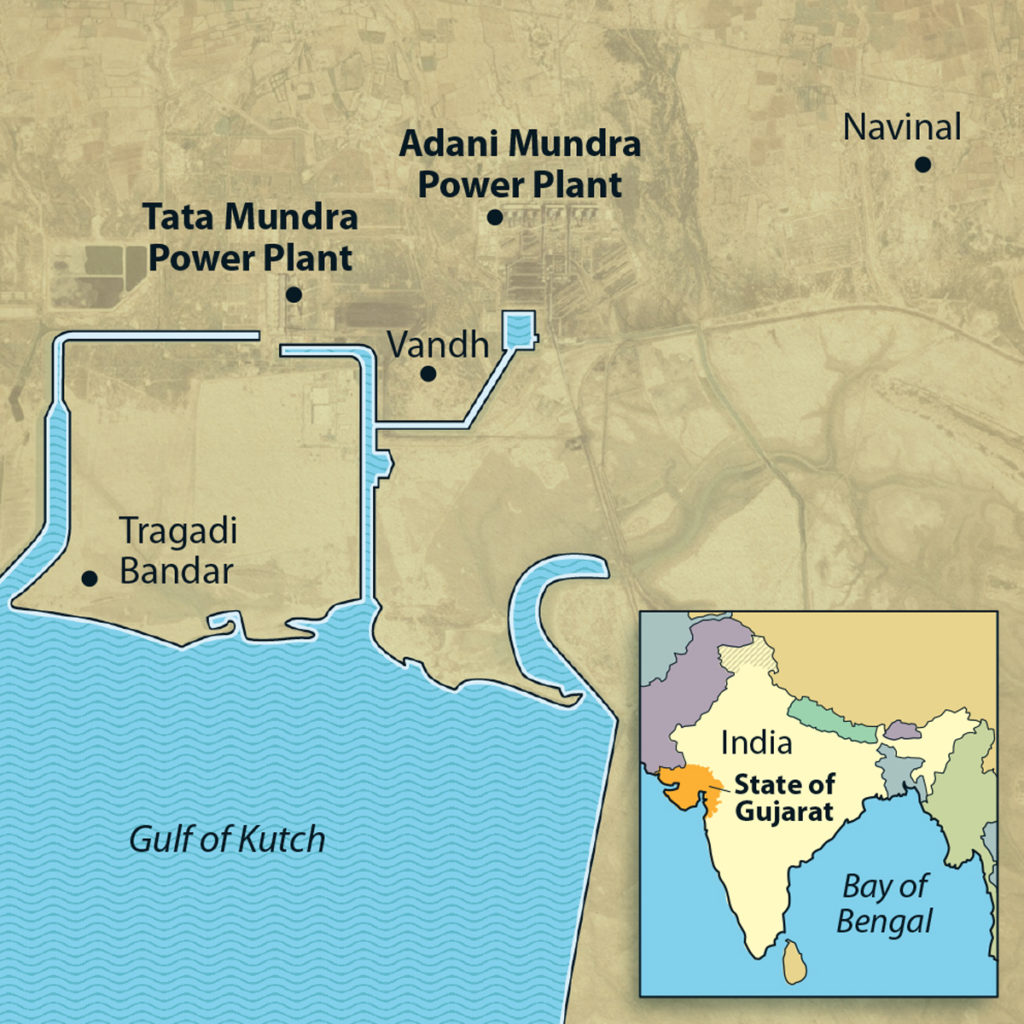

Navinal sits about five miles from the Adani Mundra plant and just a few more miles from the Tata Mundra “ultra mega power project,” built by the Tata Group, a multinational corporation and one of India’s largest conglomerates.

Jadeja takes my pen and paper and draws a map–tracing an outline of the Tata Mundra plant and marking the many small villages and fishing communities that surround it. “These people, their livelihoods, were finished.”

In 2004, just a few years after the Gujarat state government started selling land near Navinal for cheap, it established 40 square miles of nearby coastline as a “special economic zone.” That made it easier for steel factories, coal power plants, and other industrial operations to do business along the coast, even if it meant displacing fishing communities. Construction of the Adani Mundra plant started in 2006; the even more massive Tata Mundra project–made possible by a $450 million loan from the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a branch of the World Bank–followed in 2008.

“After construction, the groundwater mixed with the salty water from the ocean,” Jadeja says. “Farmers are no longer able to grow crops on roughly half of the farmland in Navinal village.” On the map, he points to where the Tata Mundra plant’s outflow channel releases heated wastewater from the 4,150-megawatt operation.

Fisherman Budha Ismail Jam is the lead plaintiff suing the international finance corporation, the private lending arm of the World Bank. Photo by Sami Siva/Redux

Some days, the villagers in nearby Vandh wake up to coal dust on their roofs and yards; sweeping it up is their first morning chore. They live behind a six-foot cement wall adjacent to a large pile of coal, near a conveyor belt transporting coal from the nearby port. All that coal dust and fly ash has tainted the area’s land. Jadeja says farming has decreased by at least 30 percent since 2009. The groundwater, he says, is no longer drinkable. The local government, the Navinal Panchayat, began purchasing water from outside the village, and now the Tata Group brings in tanker trucks with potable water.

Jadeja and a handful of village leaders in Gujarat, including a 58-year-old fisherman named Budha Ismail Jam, are working to hold large-scale developers like the Tata Group and its funders accountable for ruining the local ecology, and their livelihoods. Through grassroots advocacy, environmental activism, and the help of legal strategists in academia and overseas, these villagers have not only pressured Tata to clean up its act but also managed to sue the IFC, which is based in the United States, over its role in building the Tata Mundra plant–and even advanced their suit all the way to the US Supreme Court.

In October 2018, the Supreme Court heard Jam v. International Finance Corporation to determine whether the villagers had the right to sue the IFC–a potentially precedent-setting case. At the end of February 2019, the court ruled in favor of Jam et al., kicking the case back to the lower court. The decision, which has broad implications for environmental law, will make international organizations like the IFC more accountable for the environmental and public health impacts of their projects, not just in India but around the world.

Bharat Patel works for a trade union in Gujarat, advocating for fisher rights and fair wages in the region’s many fishing communities. We bounce along an unpaved road to a makeshift settlement called Tragadi Bandar, near the Tata Mundra plant, on our way to meet up with Jam. As we drive, Patel occasionally opens the door to spit gutka (chewing tobacco), when he’s not juggling one of his two phones.

“This is a people’s movement–a people’s struggle–that got this global institution [the World Bank] to sit up and recognize the things that they are doing.”

Indian politicians had sought to industrialize Gujarat when they established special economic zones. Prime Minister Narendra Modi may have bolstered such efforts nationwide when, after his election in 2014, he announced a master plan to provide electricity to all Indian homes by March 2019.

According to Patel, few if any of the resulting projects took into consideration their potential environmental and public health impacts. As he drives me around the Kutch district, he points out the many other new plants in the area–steel, wind power, thermal power–and says that there are now 50 to 60 industrial plants along the coast of Kutch. “This is a big struggle for the fisherpeople and folks who live on the coast,” he says.

While coal is proving to be a cheap source of electricity, the coal plants haven’t translated into infrastructure or other investments for the region. The roads around the Tata Mundra plant remain unpaved, and other areas are largely undeveloped. People rely on the soil and the sea to eke out a living.

We pass women carrying pots of water on their heads, collecting firewood for cooking, and cutting grass to feed their animals. Cows occasionally take over the road, jockeying for position with drivers. We dodge a horse-drawn cart as we make our way past one side of the Tata Mundra plant and then turn onto a dirt road next to the massive outflow channel.

Running the Tata Mundra plant requires roughly 4 billion gallons of seawater from the Gulf of Kutch each day, which may be contributing to mass die-offs of fish. The water is processed, then discharged back into the sea through the four-mile-long, 820-foot-wide outflow channel. Its creation required the area to be dredged, which precipitated a decline in fish stocks and turned coastal settlements into peninsula communities, surrounded on both sides by channels. Many villagers are now cut off from the road leading to the area’s few shops.

Bharat Patel works for a fishing trade union. Photo by Lakshmi Sarah

At Jam’s family compound, fences made from sticks, draped with drying fish, form barriers that separate the residence from others nearby. The structures are temporary, made up largely of branches and sewn-together burlap bags. A slight breeze carries the smells of salty sea and fresh-caught fish. Several women are busy sorting the catch.

Jam, who has a kind smile and a gentle demeanor, wears white from head to toe. His white topi, or prayer cap, is common attire for many Muslims in this region. His five sons, two daughters, and 16 grandchildren all contribute in some way to the family fishing business–catching, sorting, drying, or processing. We sit down within sight of the gulf. The tide stretches out beyond the sand, the mud dotted with temporarily abandoned fishing boats. As the sun sets, the lights on the towering smokestacks of Tata Mundra, clearly visible, wink at us.

The IFC funneled its first loan to Tata in 2008. In 2011, Patel and the fishers filed a complaint with the ombudsman in charge of loan compliance. “We called Joe. . . . With the whole community, we had meetings,” Patel says, referring to a series of events that started in 2009.

Joe Athialy is the executive director of the New Delhi–based Center for Financial Accountability and was instrumental in helping to connect the plaintiffs to a broader audience. Athialy is no stranger to grassroots movements, nor to the politics of large-scale development projects. He was active in the Narmada Bachao Andolan, or Save the Narmada movement, which fought dam development in India in the 1980s.

With Athialy’s help, Patel and Jam sent a petition to then–World Bank president Jim Yong Kim, demanding that the World Bank recognize the IFC’s environmental policy violations in building the Tata Mundra plant and “develop remedial action that has a clear timeline.” Their petition, asking that the bank immediately withdraw funding from the Tata project, netted almost 30,000 signatures–the first time an Indian petition arrived at the World Bank bearing so many.

Patel and fellow community members also brought some of their complaints to India’s national green tribunal–an environmental protection forum established in 2010. They managed a brief win in 2012: The tribunal ordered Tata to halt another nearby coal plant’s damaging operations. Yet, after receiving environmental clearance, the plant resumed operation in 2015. For its part, Tata started providing potable water twice weekly but did nothing else. So Patel and the villagers decided to shift their efforts to the US legal system.

Hunter believes that Jam v. International Finance Corporation represented “one of several moments where the voice of ordinary citizens got to reverberate in the international law system.”

Since he became the lead plaintiff in the legal case against the IFC, Jam alleges, the Tata Group has offered him money, contract work, and even a new boat to drop the suit. Before he left on the hajj pilgrimage, he claims, the company promised him six lakhs (around $10,000). “So many times they came,” Jam says. “Two, three times they offered compensation to drop the case.”

Meanwhile, his family’s livelihood has continued to suffer because of the impact the Tata Mundra plant has had on the region’s marine ecosystem. Jam’s wife, Mariam, says that back in 1999, they used just one boat to fish.

To get the same yield now, she says, it takes four.

As Patel, Jam, and the fishing communities along the Gulf of Kutch continued to fight the IFC and Tata for reparations, their story began to reverberate in faraway places.

In December 2014, two people showed up in Tragadi Bandar asking questions: Rick Herz, a senior litigation attorney, and fellow staff attorney Michelle Harrison, both with the D.C.-based nonprofit EarthRights International. The more they learned, the more they realized that the villagers were in an unusual situation. The IFC had been founded in 1956, just over 10 years after the World Bank, with lofty ideals–the projects it funded were intended to lift people out of poverty, not destroy ecosystems and livelihoods. And to Herz, it was clear that the IFC had ignored its own research when it funded the coal plant.

Map by Peter and Maria Hoey

What many of the local villagers didn’t know was that the construction of the Tata project should never have started–in part because of the World Bank’s own warnings about the plant’s potential environmental impact. Before confirmation of the loan, the IFC was obligated under standard procedure to conduct its own review; in 2006, the World Bank stated that the project was “expected to have significant adverse social and/or environmental impacts that are diverse, irreversible, or unprecedented.” Despite these early warnings, the Tata Mundra project went forward.

The IFC states that its mission is to “carry out investment and advisory activities with the intent to do no harm to people and the environment.” But by that criterion, say Jam and others, “the Tata Mundra plant is thus a mission failure.”

But whom to hold accountable for this failure, and how?

Herz says that the EarthRights team became involved because of the scale of the harm and because of the IFC’s “obvious disregard of its own policies.” The IFC’s internal accountability arm, he reiterates, found that the plant indeed was hurting the villagers–”the very people it is chartered to help.”

With help from Athialy and EarthRights International, Jam and Patel formally launched a class action complaint in April 2015 in the US District Court for the District of Columbia, not far from the IFC headquarters. The IFC responded a few months later with an immunity defense, claiming that the suit must be dismissed in its entirety because groups like the World Bank were exempt from prosecution under a 1945 statute called the International Organizations Immunities Act.

In 2016, the court agreed that the IFC enjoys “absolute immunity” and dismissed the case; a year later, a three-member panel of the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit upheld the decision. Then, in the spring of 2018, the Stanford Supreme Court Litigation Clinic stepped in to help Jadeja, Jam, Patel, and EarthRights International get their suit all the way to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court agrees to hear about 100 to 150 cases per year out of more than 7,000 requests. The plaintiffs from Gujarat had every reason to believe, when they submitted a cert petition, that the highest court in the United States would decline to hear their case. Nearly everyone involved was surprised when, instead, the court accepted their petition.

The court considered only one part of the case. According to Marco Simons, the regional program director and general counsel for EarthRights International, it came down to this: “The question isn’t ‘Who was harmed, by how much, and who is responsible for it?’ It is ‘Should these institutions be above the law, and are they subject to any kind of accountability?’ Which is really the same question that the communities have been asking for a decade now.”

At the October hearing, the courtroom was crowded; the acoustics of the 1935 architecture made it difficult to hear the judges behind the bench. For Athialy and Patel, who had come to Washington to attend the hearing (Jam and Jadeja stayed home in Gujarat), the red drapes and regal white pillars decorating the high court were in stark contrast to the sand and water of Tragadi Bandar.

During oral proceedings, the lawyer for the IFC–Donald Verrilli Jr., solicitor general during the Obama administration–argued that if the plaintiffs won, it would unleash a flood of lawsuits against organizations that, like the World Bank, are only trying to help raise global standards of living. The IFC, Verrilli claimed, should have absolute immunity from such suits.

A surprise counter to that argument came from the Trump administration–assistant to the US solicitor general Jonathan Ellis appeared in court as a “friend” in support of the plaintiffs, objecting to the notion that international organizations should have absolute immunity. In addition, a bipartisan group of Congress members wrote a brief supporting the Indian fishers.

The oral arguments were quick–the two sides took just an hour to battle over the fate of absolute immunity.

Among the Gujarati fishers, their lawyers, and the crowd of environmentalists and activists present, there was a palpable sense of victory–the case had come this far. “If [the IFC] feel that it is going to open up a floodgate of cases,” Athialy said, “then they were doing something wrong altogether.”

Then in February, the Supreme Court sided with the plaintiffs in a 7–1 decision, ruling that international organizations like the IFC do not enjoy “virtually absolute immunity” and therefore can be sued. Simons says the case will now be remanded to the D.C. circuit court, which will decide whether to rule on the merits (damages done to the fishing villages of Kutch, for example). However, he believes the case may be settled before then. “We would hope that the IFC would simply choose to sit down with us and provide the remedies that we’re asking for, rather than continuing to fight it out in court.”

Even before the Supreme Court decision, the case had led to changes at the IFC. The lender eliminated funding for fossil fuel plants, which, according to David Hunter, a professor at American University’s Washington College of Law, indicates that the case has changed how the IFC’s senior bank staff approach environmental and social issues. Other possible explanations include concern for bad PR and further lawsuits and the fact that coal power plants don’t net the financial returns they once promised. Regardless, Hunter believes that Jam v. International Finance Corporation represented “one of several moments where the voice of ordinary citizens got to reverberate in the international law system.”

Still, the World Bank continues to advance coal projects through intermediaries like Indian banks that do the direct investment and through associated infrastructure such as ports or transmission lines. “It’s a kind of mask that they are using–a facade, basically,” Simons says. Case in point: One 2016 study by Inclusive Development International found that the IFC had given loans to intermediary banks funding no fewer than 41 coal-based projects in India.

As Jadeja, Jam, Patel, and Athialy await the next step, they have been filing complaints with India’s pollution control board and meeting with others engaged in similar battles. Athialy is hopeful that the case will empower communities around the world to challenge the World Bank and says it could become a major tool for those seeking to advocate through legal means.

“This judgment will strengthen communities’ efforts to hold the bank accountable and is a step in the direction of bringing accountability in financial institutions,” he says. “This is a people’s movement–a people’s struggle–that got this global institution [the World Bank] to sit up and recognize the things that they are doing.”

Regardless of the outcome of the case in the lower court, the plaintiffs–who plan to submit a complaint to the Asian Development Bank–will persist. “We don’t have any other alternative than to continue the struggle,” Patel says.

Back in Tragadi Bandar, daily life remains the same. The groundwater is still polluted, and fish stocks are in steady decline. Still, Jam’s sons go out to catch the fish, bring them home to sort and dry, and start anew each day.

The article, first published on the Sierra Magazine, can be accessed here.