Under the Paris Climate change accord, India has committed 40 per cent of its total energy production from non-fossil fuel sources by 2040

The Centre has also decided to set up mega solar parks that will have own transmission systems

Nestled inside a highly-guarded building at the Qutub Institutional Area in Delhi, power system operator POSOCO can sense the nerves of the country’s green power generation.

Eleven renewable energy management centres (REMCs) have plugged into a new centre. These are part of the government’s plan to seamlessly integrate renewable energy (RE) with conventional power for stability of the electricity grid. The building for the northern region centre is under construction but a supplementary unit next to the existing POSOCO centre has started tracking RE in India. The REMC is equipped with real-time weather forecast that uses satellite imaging of clouds. It gives live updates of the load profile of all solar and wind projects. It collects generation data, predicts generation for the next day or even the week and plans its despatch. It takes Rs 15-20 crore to set up one REMC. The one for the western region is already functional.

The centre sure looks impressive but the data doesn’t. Of the 98.76 billion units of energy supplied across the country in December, solar and wind comprised only 9.5 per cent. During April-November 2019, RE was 8.2 per cent of the total energy generation in the country.

Under the Paris Climate change accord, India has committed 40 per cent of its total energy production from non-fossil fuel sources by 2040. But it has not committed to reduce its coal-based power. Thermal power still has close to 80 per cent of India’s power generation. Renewable power, however, has disrupted the sector. Grid managers are the first to face this. Wind energy runs for few months in a year and solar only for six to eight hours a day. Besides, these units are confined to certain regions of the country.

At the company level, monitoring the intermittent nature of renewable power has also started. At Okhla, Hero Future Energies has a remote monitoring centre. Data generated by drones tracks the company’s projects across 10 states which helps in forecasting and scheduling of power.

The first challenge for generators like them is to transport power to the nearest sub-station and the next is to transmit to other regions. To address this, the Centre announced Green Energy Corridors (GEC) – dedicated transmission network for renewable projects.

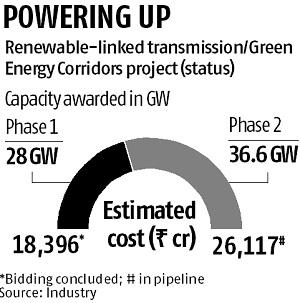

The progress in this project has been slower than the rate at which generation projects are coming up. In the first phase of the GEC, around 20 Gw of transmission capacity is being built by state-owned Power Grid Corporation of India.

Data suggests that so far only two projects in Tamil Nadu and Rajasthan have come up. Another 20 Gw was bid out to private companies. There is an additional 66 Gw, which was planned to be constructed to connect renewable projects, of which bidding for 28 Gw has concluded.

The Centre has also decided to set up mega solar parks that will have own transmission systems. The anchor firms will build the internal transmission system, which would make the power from units located inside the parks costlier by 30 per cent. Some of the renewable power companies are, therefore, investing in transmission. Several technologies are being used to improve supply and optimise generation from their plants.

Goldman Sachs-promoted ReNew Power has entered the transmission business, too. In August, ReNew bid for projects worth Rs 1,500 crore. However, it didn’t win any. “Moving into transmission was a natural progression as the firm has an extensive network of generation projects and it is cost effective to build own transmission,” said Ajay Bhardwaj, president, transmission, ReNew Power.

India’s largest power generating company, NTPC is looking at a different strategy. It is setting up solar power plants at its existing thermal sites. The capacity of each solar unit will be close to 200-500 Mw and the total target is 10,000 Mw.

Sector players say renewable would not be an alternative to fossil fuel despite the multi-pronged approach. Delay in adoption of tariff for RE projects by some of the state electricity regulatory commissions leads to uncertainty in the sector. Then, there is delay in payment by some power distribution companies (discoms). The reported dues of the discoms to RE power projects stood at Rs 9,000 crore in December 2019.

While India aims for 175 Gw of renewable power generation by 2022, which is now barely two years away, doubts around renewable still prevail. With the rampant growth of RE generation projects, most these plants would find it difficult to get returns in a few years. At times, there is no transmission network, other times, the states do not pay. It is time the planners wake up to the reality of ‘too much renewable energy and less transmission’ and build a robust mechanism.

This story has been published with support from Smitu Kothari Fellowship Program-2019

The article is published in Business Standard.