This year, the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meeting on October 12-13 overlapped with the IMF-World Bank annual meeting on October 13-15 in Washington, DC.

As of December 1, 2017, Argentina becomes G20 President with the past and future Presidents (Germany and Japan, respectively) as part of the G20 Troika. At the October G20 meeting, Argentina announced that it’s two key G20 Finance Track priorities will be the Future of Work (shared with the Sherpa Track and possibly looking at automation, education, and womens’ entrepreneurship as well) and Infrastructure Financing, especially through financialising infrastructure as an asset class. The priorities of the Argentine Sherpa Track will be announced at the final German Sherpa Meeting on 9-10 November in Berlin.[1]

The individual G20 member countries hold the overwhelming majority of votes at the IMF and World Bank, so it is not surprising that G20 priorities are often identical to those of the institutions they dominate. For example, infrastructure financing has been a G20 development theme since 2010 and a powerful Finance Track theme since 2014, except under Germany, when infrastructure issues were dealt with by the Sustainability Working Group and under the Compact with Africa.

Since 2010, the G20 has focused urging the Multilateral Development Banks to standardize, scale-up, and replicate mega-projects, especially public-private partnerships (PPPs) in emerging and developing countries. Indeed, the G20 encouraged the strengthening of existing and start-up of new Project Preparation Facilities (PPFs) with the capability of accelerating mega-project preparation — especially for trade facilitation in the energy, water, transportation and ICT sectors. In each geographical region and subregion, Master Plans for Infrastructure in these four sectors have already been designed.

Especially since 2014, the G20 has tried to solve the problem of how countries can attract private investors, particularly long-term institutional investors (pension and insurance and mutual funds and sovereign wealth funds) which hold over $100 trillion in savings. While the G20 and the MDBs have not succeeded in mobilizing much additional financing for PPPs from investors, efforts to overcome remaining obstacles are described in Boxes 1 and 2.[2]

Until the German Presidency, there was no effort to promote infrastructure that would be environmentally and socially sustainable. Even under the German Presidency, the officials leading the powerful Finance Track said that sustainability is the job of the (less powerful) Sherpa track. Infrastructure contributes approximately 60% of greenhouse gases (GHG) emitted to the atmosphere; therefore, it is crucial that urgent steps be taken to curtail infrastructure that locks-in carbon-intense technology and ensure that infrastructure meet criteria for mitigation of GHG and adaptation to the effects of global warming. At present, all such criteria are voluntary whereas the rights of investors are legally protected in trade/investment agreements and the PPP contracts that include investment provisions.

|

Box 1: New infrastructure-related institutions

The G20 has directed each multilateral development bank to expand infrastructure financing for years, especially by “crowding in” the private sector. At the Hamburg G20 Summit in July, Leaders adopted principles to achieve this.[3] These principles underpin the theme presented at the IMF/World Bank annual meetings — namely “Maximizing Finance for Development” (also known as the “Cascade” or “billions to trillions”). The October 14 Communique of the Development Committee emphasizes this theme, which is actually a relatively new paradigm for financing infrastructure.[4] The IMF and World Bank’s two papers[5] for the Development Committee meeting describe this paradigm and its implementation.

While the World Bank is tasked with expanding private investment in infrastructure, the IMF’s Infrastructure Policy Support Initiative provides tools to help countries assess the macroeconomic and financial implications of various investment programs and improve their institutional capacity.

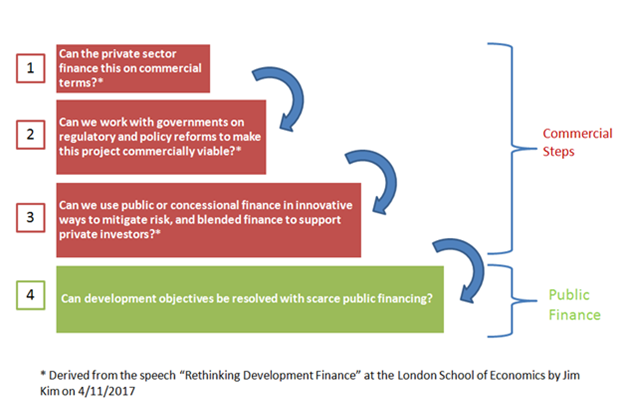

The gist of the “Maximizing Finance for Development” paradigm is that nothing should be publicly financed if it can be commercially financed AND that if commercial financing is NOT forthcoming for a project, a country must promote a more investment-friendly environment and/or private sector guarantees, risk insurance and other inducements should be provided. My blog criticizes the paradigm[6], which relies heavily on expanding the launch of PPPs, including by packaging them in portfolios for trading.

Figure 1: Maximizing Finance for Development (“the Cascade”). Creator: Jim Yong Kim, Speech at LSE 04/11/2017.

There are Cascade pilots in nine countries (Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Egypt, Indonesia, Iraq, Jordan, Kenya, Nepal and Vietnam) which are intended to introduce private sector solutions in energy, transportation, and other infrastructure sectors. The pilots will gradually expand to include other sectors and countries.

The “Maximizing Finance for Development” paradigm responds to the G20 interest in attracting private investors, especially long-term institutional investors such as pension and insurance and mutual funds as well as sovereign wealth funds. As it is, OECD pension funds ($30 trillion) and insurance funds face staggering gaps and potential insolvency unless they can get higher yields on their savings. Many long-term institutional investors, such as pension funds, will work with hedge funds and private equity funds to deploy their assets under management (AUM) in infrastructure portfolios for these higher yields.

The idea of this paradigm is for the public sector to take high risks at the early stages of project identification, design and construction and the long-term investors to take a revenue stream over 20 or 30 years. To counter this agenda, a Global Campaign Manifesto on PPPs was launched by 152 national, regional and international civil society organisations, trade unions and citizens’ organisations from 45 countries to “sound the alarm on dangerous PPPs.

Megaprojects and PPPs are not inherently dangerous, but when their design fails to produce adequate social and environmental co-benefits and heap risk on governments, they become so. When risk is heaped onto governments, PPPs tend to increase inequality by privatizing gains and socializing losses. The World Bank “Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions” proves how heavily the World Bank proposes heaping risk on governments as well as introducing “stabilization” procedures that would inhibit the right to regulate/legislate in the public interest. Motoko Aizawa summarizes key critical points on the Guidance and links to the legal analysis of the Guidance by the firm Foley Hoag. Despite major problems with the “Guidance” – it will be launched in Cape Town, Kuala Lumpur, and possibly Abidjan — unless the process is stopped in order to radically revise it.

| In Africa, the “Compact with Africa” report by the Africa Development Bank, World Bank, and IMF (March 2017, Baden Baden) describes how public utilities would be taken “off balance sheet” and user fees and domestic resources would be mobilized, along with aid, to shoulder public risks and, meanwhile, development banks would offer guarantees and liquidity facilities to offset risks to the private sector.

The heavy policy conditionalities proposed by the G7/G20 for each African country participating in the “Compact” include requirements that governments use the World Bank’s “Guidance on PPP Contractual Provisions” which would impose enormous risks on governments while hobbling their capacity to protect the public interest. The conditions also require that governments develop Systematic Investor Response Mechanisms (SIRMs) to satisfy investor grievances before they reach international tribunals (Investor-State Dispute Settlement). Concerns for investors are not matched by concerns for citizens who often lack even basic information about the development of projects that will affect their lives. In light of the heavier push for financialising infrastructure, we have a recent NEPAD announcement which calls for African asset owners to raise the percentage of assets under management for infrastructure from 1.5% to 5%. This strategy is aggressively promoted by Africa’s Continental Business Network (CBN), which issued a communique in September calling for the adoption of this strategy at the AU Summit in January 2018 with a roadmap presented to the African Finance Ministers meeting in March 2018 as well as the G7 and G20 Summits later in the year. |

Box 2: G20 compact with Africa

The G20 will measure the performance of each MDB by the extent to which it leverages private investment[7] and, in turn, the MDBs will measure the performance of many countries by how effectively they leverage private investment.

In conclusion, the “Maximizing Finance for Development” approach would create greater reliance on commercial financing and reduce the need for World Bank lending to governments, as would the Trump/Mnuchin push to reduce World Bank lending operations to creditworthy countries (See FT 10/13/17 “US Demands China loan rethink as condition of World Bank cash”). If these approaches are implemented, the World Bank could shrink as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (and others) expand. Potentially the finance available for public goods (stable finance, sustainable development and climate goals, urban infrastructure such as sanitation…) would become even more scarce. Privatization and deregulation would give market players, even the predators, freer rein.