Since the turn of the 21st century, the Indian state has increased its focus on using digital technologies to provide and organise government services. As information and communication technologies (ICTs) have become ubiquitous, e-governance has become more ambitious. Furthermore, the internet is rapidly becoming an integral part of almost every sector and business, from banking to education to health. The Covid-19 pandemic has made this reality stark enough. For many of us, the past year has been spent working, studying, socialising, celebrating, and grieving online. The pandemic has also brought to the fore a number of inequalities that exist, including access to the internet.

Scholars, activists, international organisations, and national governments have argued in favour of access to the internet being considered a basic right. In India, the Kerala High Court in 2019 held that access to the internet is a basic right, because without access there is an infringement on the fundamental right to education and to privacy. In 2020, after internet access was suspended in Jammu and Kashmir for more than five months, the Supreme Court ruled that “access to Internet is a fundamental right under Article 19 of the Constitution [freedom of speech and expression], subject to some restrictions”; and, further, that “freedom of press is a valuable and sacred right.”

Infrastructure and policy

But what does it take to provide universal internet access? We rarely think about how the internet reaches our homes, schools, and public places. What are the physical infrastructure, policy and legal frameworks necessary to make internet access meaningful and empowering?

The digital infrastructure is the foundation on which digital services, technologies, and the information economy are built. Such infrastructure spans hardware and software, as well as, I argue, legal frameworks that protect the data and privacy of citizens and consumers, and limit state control and censorship. Robust digital infrastructure not only strengthens government services and last mile connectivity, but also facilitates innovation in products and services. Digital infrastructure includes fixed and wireless broadband, mobile communications, cloud computing centres, storage of data, and training to manage and expand these structures. Data localisation, or the storage of citizens’ data within the geographical territory of that country, can also be considered a part of a country’s digital infrastructure. These infrastructures make the internet accessible, affordable, and decentralised. Apart from empowering and protecting citizens as users of the internet, a strengthened infrastructure could translate into the development of localised, grassroots-level digital technologies.

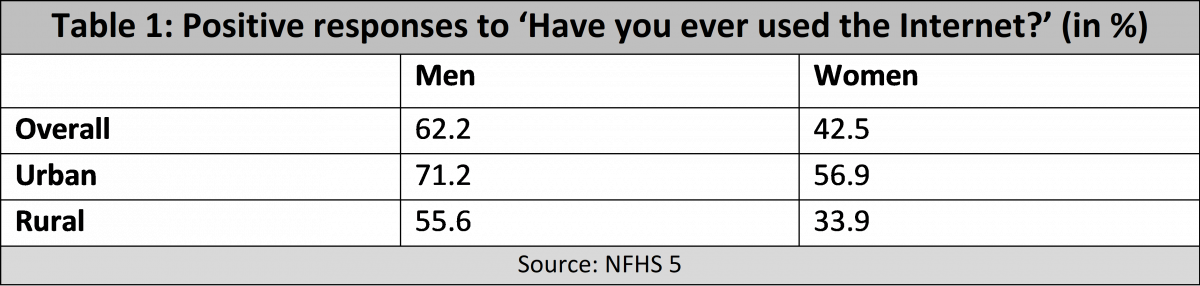

In order to realise access to the internet as a basic right, the Indian state must consider these various aspects of the digital infrastructure and how they should be built. While India is often praised for its number of smartphone users, it is impossible to overlook the country’s digital divide. Based on the latest National Family and Health Survey (NFHS 5), which released data on 22 states and union territories in December 2020, the gendered digital divide and the rural-urban digital divide are chasms, as shown by Table 1. It should be mentioned that the survey framed the question as, ‘have you ever used the internet’. This framing includes those who may have accessed the internet just once, suggesting that the actual digital divide, both along gender and location lines, might be much greater.

At the moment, the private sector is the most significant developer of digital infrastructure and provider of internet access. According to Statista.com, as of 2020, 94.64% of internet users in India subscribe to one of three private internet service providers. While this number might continue to grow in the coming years, what must be studied is where this increase is taking place and for which demography. India’s digital divide demonstrates that the private sector may not be capable of or interested in developing internet capacity in certain parts of the country. NFHS 5 data shows that even in large and supposedly well-developed states like Gujarat and Maharashtra, only 48% and 47.2% of rural men have accessed the internet, respectively. In states like Bihar and West Bengal, these numbers fall to 39.4% and 38.3%, respectively. It is then incumbent upon the state to understand what digital infrastructure is lacking and how these lacunae can be filled, especially as e-governance ecosystems grow.

In Kerala, on the other hand, while a gendered digital divide does exist, 74.2% of rural men have accessed the internet. This is only two percentage points below the state average for men. Kerala has focused on bringing internet connections to its citizens through schools, community centres, and now directly to households. The state government has taken on the responsibility of laying fiber optic cables across the state under the Kerala Fiber Optic Network Project (KFON), which will provide “internet connection to BPL [below poverty line] families, government offices, hospitals and schools,” including free internet for 12 lakh BPL families and public WiFi across the state. The government also aims to make internet access affordable and fast, to actively help bridge the digital divide. Here we see that the state government has taken on an active role in building digital infrastructure, by focusing on the hardware that makes internet access possible. The state also addresses digital literacy and inclusion by ensuring that this digital infrastructure is equitably spread out across the state rather than concentrated in certain areas.

Kerala’s approach is one way for the state to be involved in building digital capacity and infrastructure, but it is not the only way. If internet access is to be considered a basic right, the state has to play a role in ensuring universal access by treating digital infrastructure as a public good. Such infrastructure — or parts of such infrastructure — has to be expanded in ways similar to other social programmes. For other large infrastructure and for the provision of social services, India has instituted targeted and universal social programmes, initiated public-private partnerships (PPPs), and has set up subsidies for both providers and consumers of services. To build digital infrastructure and provide universal access to the internet, India will have to employ a combination of these interventions.

Right to privacy

Ensuring access, however, is necessary, but not enough. Along with it, and crucially when it comes to digital infrastructure, given its pervasive nature, India has to proactively build a legal infrastructure that protects citizens’ data and privacy. While the past five years have seen some movement towards a personal data protection law. The Supreme Court’s 2017 judgment in the Puttaswamy case ruled that the right to privacy is a fundamental right guaranteed by the Constitution. Following this, the government set up the Srikrishna Committee on Data Protection, which submitted a draft Personal Data Protection Bill in 2018, a version of which was introduced in Parliament in 2019, but has not been passed . Meanwhile, the government has introduced various rules pertaining to digital technologies and platforms such as the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 which can have significant consequences for surveillance and censorship. India has already gained infamy for its large number of internet shutdowns.

Apart from foregoing its own responsibilities, the state is easing the exploitation of citizens’ data by the private sector. There are numerous examples for this, ranging from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) inviting tenders from the private sector to create an Automated Facial Recognition System (AFRS), to the creation of a Data Marketplace where data can be bought and sold, as discussed by various policy literature including the DataSmart Cities Strategy and the 2018-19 Economic Survey. The latter recommends the merging of government data sets and the use of data for citizen welfare, as well as the commercialisation of data for private firms and the selling of data to analytical firms. It should be noted that the Economic Survey considers data, including citizens’ data, to be a public good, but not digital infrastructure or internet access. Private sector firms are also involved in providing free public WiFi and developing government apps and platforms like the India Urban Observatory. Not only is there no law to ensure data privacy and protection against surveillance, there are also no transparent terms of functioning that give clarity on the data that these firms can access and what they might do with it. Further, the central government usually works with the same small set of corporations without a formal tender thus increasing conflicts of interest.

As stated above, digital infrastructure is not only the hardware and software required to make the internet widely accessible and affordable, it also includes policy and legal frameworks that make this access safe and meaningful for citizens. Digital infrastructure in India should be built on a foundation of certain democratic principles and priorities that protect citizens’ rights, safeguard against state overreach in terms of surveillance and censorship and prioritise data security over monetisation and corporate access. The lack of a data protection law in India leaves citizens exposed to state and corporate exploitation. While the state might build digital infrastructure and continue to expand e-governance facilities, without policy infrastructure that keeps the welfare of citizens at its centre, access to the internet will never be a transformative tool that could lead to the deepening of democracy and various freedoms like the fundamental rights to privacy, education, freedom of speech and expression, and the right to participation.

This article was first published in The India Forum

Picture courtesy: Times OOH/Flickr