What better time to bring into effect the Labour Codes than right after a thumping victory in the Bihar elections. Bihar, a labour-sending state, saw out-migration, “palayan” of youth, lack of employment opportunities and low wages emerge as major issues in the run up to the elections. Yet, when a thumping victory came its way, the irony is not lost in the government bringing into being a virulently anti-labour set of codes that it had been waiting to set in motion for several years.

What better time to bring into effect the Labour Codes than right after a thumping victory in the Bihar elections. Bihar, a labour-sending state, saw out-migration, “palayan” of youth, lack of employment opportunities and low wages emerge as major issues in the run up to the elections. Yet, when a thumping victory came its way, the irony is not lost in the government bringing into being a virulently anti-labour set of codes that it had been waiting to set in motion for several years.

The codes beyond the details marks a significant shift in the fundamental relation or social contract between the state, capital and labour. It institutionalises the role of the state more as facilitator than a protector of labour rights wherein it merely calibrates labour rights based on market demands as envisaged by the reforms that began in 1991.

The codes take away our rights

While most of the media houses and editorials have celebrated the Codes, a close reading reveals that crucial issues like floor wage, safety limits or social security thresholds are no longer written into the text of the Acts. They are rather only in the Rules which can be altered at will easing the path for a race to the bottom for the states as they compete with each other in diluting labour rights to attract capital. This leaves workers without enforceable and inalienable rights.

Earlier to legally exercise a hire and fire policy an establishment needed to employ less than 100 workers. The Codes arbitrarily raise the threshold to 300 thereby in one stroke exempting over 90% of India’s industrial units from scrutiny, allowing hire and fire at will. The Code mandates the Union government to fix a floor wage, which sounds positive on first glance, but the floor wage does not need to be subsistence wage any longer. They do not need to correspond to nutritional and consumption standards paving the way to poverty wages. At a time when there have been demands for a living wage and decent wage, we seem to be going a step back.

While the Code retains the 8-hour daily work limit, it covertly introduces the idea of 12 hour shifts as it introduces the concept of “spread-over” time. This can allow state governments to legally stretch the workday to 12 hours. Comrade Thomas Franco reminds us that it was in 1919 that the International Labour Organisation had passed its First Convention—The Hours of Work Convention—which brought the ‘Application of the Principle of 8-hour working day’. It is shameful, he says, that after a hundred years, the Union government wants to change this and a few states have already done the same.

There are talks of social security for gig workers, but as Arun Kumr points out, they would mean little if exploitation is allowed to increase. Also, the code still doesn’t recognize them as employees and they don’t have a right to pension, for instance. The code does not speak up against outsourcing which has been a potent tool in the hands of the government to convert government jobs into contractual work. Workers, economists and even the Supreme Court recently has said that outsourcing cannot become a convenient shield to perpetuate precariousness. Banks have been forced to undertake several such outsourcing to do cost cutting and shed staff weight which is unacceptable. Also the ILO Conventions 87 and 98 that speak of freedom of association and right to bargain have been concerns that the AIBOC has been raising for years now, without avail. The Codes too remain silent about these and instead there is only a bragging about “simplification” of earlier laws which it is said will improve private investment. But as Arun Kumar points out, private investments have been low due to faulty policies (like demonetisation and GST) and lack of demand in the economy. Weakening labour will only aggravate the demand problem.

All the central Trade Unions except BNS have vehemently rejected the Codes and have criticized the way in which tripartite consultations and procedures were flouted to push through the codes. It is rather shameful that the Indian Labour Conference (ILC) – the apex mechanism where government, employers and workers deliberated policy – has not been convened since 2015. The unions including NTUI have criticized the unreasonable restrictions on forming and joining unions. Apart from complicating union registration, it also limits which unions can represent workers. Workers are now required to provide a 14-day notice prior to a strike and strikes are prohibited during conciliation proceedings. These nearly impossible conditions for lawful strikes—restricts workers’ constitutional right to collective action and association.

Tariff crisis only an excuse

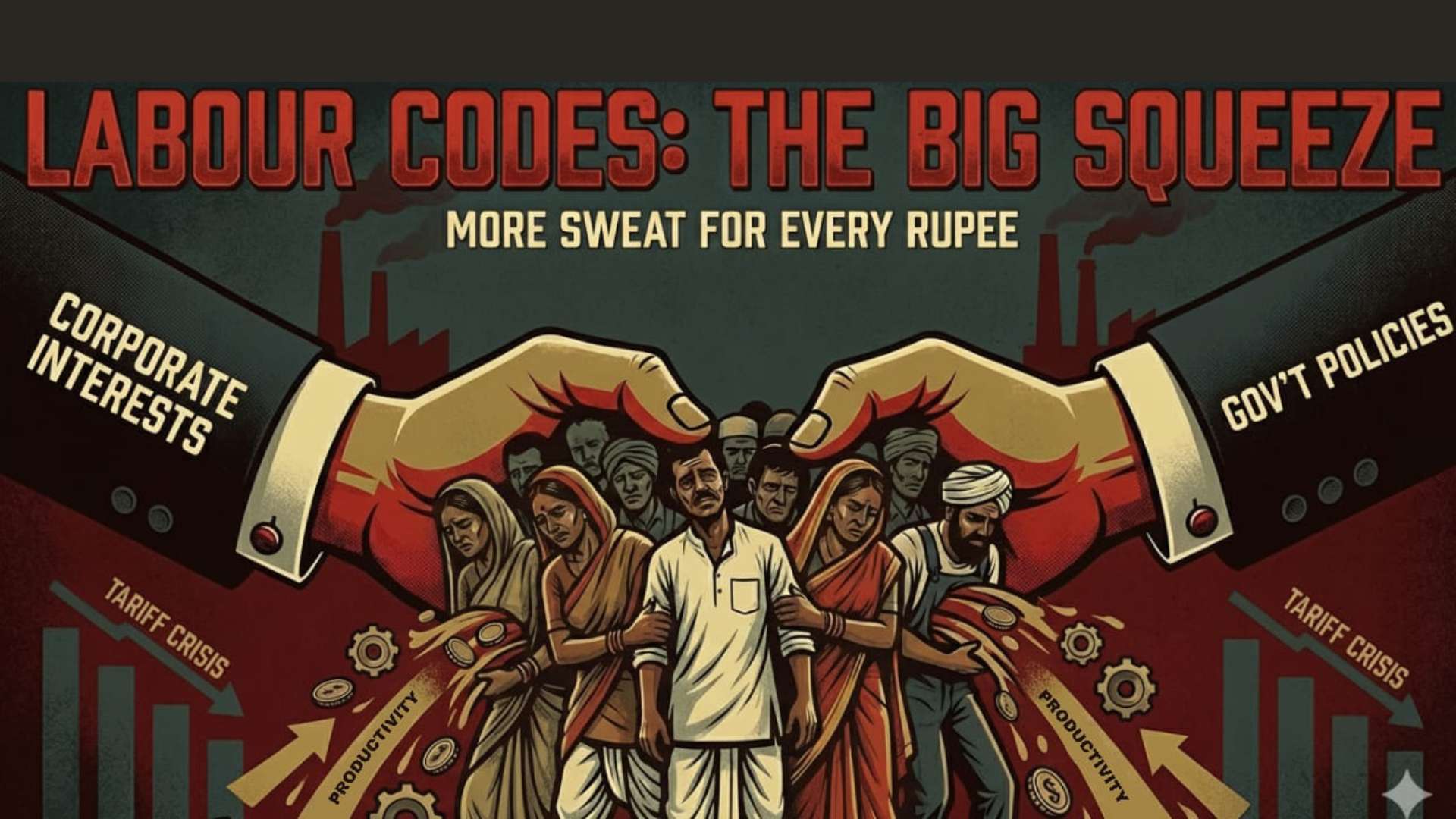

There were ample clues though that this was coming and it is rather clever on the part of the government to use the excuse of the geopolitical tensions, the fall in exports and the tariff crisis to make way for these anti-labour codes. The last Economic Survey had stated that in the absence of export-driven growth and given the apprehensions about falling foreign direct investments, “we need to intensify our efforts on the domestic front” and concentrate more on the “efficiency” of investments. That is the only way, it says, of maintaining the levels of high GDP required to achieve the status of ‘Viksit Bharat’ by 2047. Who needs to sacrifice for this? Not India’s corporate sector that is celebrating record breaking profits and refusing to share the same with workers. The scapegoat is our labour.

How can “efficiency” be improved? The Economic Survey answers: “By reducing the time taken for investment to generate output and by generating more output per unit of investment.” In other words, we need to attain the ‘Viksit Bharat’ status by following a growth path that squeezes labour. The survey argued how regulations meant for protecting workers in fact act against them and their supposed “long term” interests. As firms try to avoid such complaints, they tend to stay informal and avoid scaling up, it says. This, it says, in turn discourages job creation, limits wages and encourages informal employment. As a result, it advocates the removal of hard earned labour rights. Similarly, it said that our compliance and inspection based regulatory framework is not realistic and is better done away with. As an example it cites that only “644 working inspectors are available to oversee compliance in 3,21,578 factories, with each overseeing around 500 factories”. However, while several labour rights activists may quote the same figures to argue for more inspectors, the economic survey argues in favour of doing away with such “unrealistic expectations”. In other words, our path towards a ‘Viksit Bharat’ needs to pass through sweat-shops and unregulated hours where the maximum can be squeezed per unit of investment.

The Labour Codes “achieve” precisely the same. It replaces the traditional “Labour Inspector” with an “Inspector-cum-Facilitator”. And the employers in case of violations can now simply pay a fee to avoid prosecution which basically is tantamount to monetising illegality. You can now pay your way out of labour rights violations. All of this is symptomatic of the idea of “ease of doing business” as the government says it needs to “unclog the regulatory cholesterol” to allow for more investments. For which it claims that workers rights need to be trampled, for their own good.

But as Comrade Rana Mitra of AINBEA says this logic is completely unfounded. He refers to the Lucas Paradox wherein Prof. Robert Lucas, showed in 1990 with innumerable, irrefutable empirical evidence that in any country, the investments – both by Private and Public – do not depend on the relaxation of labour laws, low wages, so called ease of doing business. But on the health, education, and overall well being of workers.

This article was originally published in Bank Beats (AIBOC Magazine), and you can read here.