Excerpt from Wild Fictions By Amitav Ghosh

‘Trees were my teachers,’ wrote the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, and if there is any place on Earth that could say the same of itself, it is Ternate, a tiny island in the archipelago that was once known as the Moluccas or Spice Islands. It is now part of the province of North Maluku, in the far eastern reaches of Indonesia. The seas here are dotted with volcanic islands and Ternate is one such; the surface of the island is nothing but the gently sloping cone of a volcano, Mt Gamalama, which rises from the seafloor to a height of over 5,000 feet.

‘Trees were my teachers,’ wrote the German poet Friedrich Hölderlin, and if there is any place on Earth that could say the same of itself, it is Ternate, a tiny island in the archipelago that was once known as the Moluccas or Spice Islands. It is now part of the province of North Maluku, in the far eastern reaches of Indonesia. The seas here are dotted with volcanic islands and Ternate is one such; the surface of the island is nothing but the gently sloping cone of a volcano, Mt Gamalama, which rises from the seafloor to a height of over 5,000 feet.

Ternate is a place that would, by most reckonings, be considered very far removed from the pathways of history. But the island was, in fact, a driver of global history for many centuries, as will be evident to anyone who sets eyes on the innumerable colonial forts that line its shores. The reason for this was a uniquely valuable tree that happened to grow on Ternate and the islands around it: Syzygium aromaticum, the tree that produces the clove.

This spice, which was once immensely valuable, made Ternate prosperous and powerful for hundreds of years. But in the sixteenth century, at the beginning of the era of European colonization, Ternate’s ‘tree of life’ also brought disaster upon the islanders. Various groups of European colonizers fought over Ternate and its surrounding islands in the course of a bloody struggle to establish a monopoly over the trade in cloves. The Dutch eventually prevailed, and in the seventeenth century they turned the island into a colony and decreed that henceforth cloves would only be grown on another island, in the southern Moluccas. The people of Ternate were forced, by the terms of a Dutch-enforced treaty, to ‘extirpate’ every clove tree on their island. The tree that had been Ternate’s teacher would not return to the slopes of Mt Gamalama until the next century, when cloves were already being cultivated elsewhere and had drastically declined in Value.

Today Ternate is a sleepy, quiet place, notable mainly for the ruins of the early Portuguese and Dutch forts that line its shores. But despite its remoteness from the great centres of contemporary trade, Ternate is by no means a laggard in globalization. Indonesia is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world and evidence of this is visible everywhere on the island: in the great mass of vehicles, large and small, that throng its streets, and in the fast-rising buildings that dot its villages. Indeed there is no better proof of Indonesia’s rapid acceleration than its ability to deliver an abundance of goods and services to this distant corner of its territories. But Ternate’s landscape possesses an additional marker of this era of acceleration. This too is etched upon its landscape by the island’s tree of destiny. Across the island, clove trees are dying; in orchard after orchard they stand in drooping clumps, their branches leafless, their trunks ashen. On the slopes of the volcano, clusters of dead trees can be seen, their leaden colours contrasting vividly with the greenery.

Today Ternate is a sleepy, quiet place, notable mainly for the ruins of the early Portuguese and Dutch forts that line its shores. But despite its remoteness from the great centres of contemporary trade, Ternate is by no means a laggard in globalization. Indonesia is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world and evidence of this is visible everywhere on the island: in the great mass of vehicles, large and small, that throng its streets, and in the fast-rising buildings that dot its villages. Indeed there is no better proof of Indonesia’s rapid acceleration than its ability to deliver an abundance of goods and services to this distant corner of its territories. But Ternate’s landscape possesses an additional marker of this era of acceleration. This too is etched upon its landscape by the island’s tree of destiny. Across the island, clove trees are dying; in orchard after orchard they stand in drooping clumps, their branches leafless, their trunks ashen. On the slopes of the volcano, clusters of dead trees can be seen, their leaden colours contrasting vividly with the greenery.

The farmers who tend to the trees are unanimous about the cause of the trees’ demise: the climate has changed in recent years, they say; there is less rain and it falls more erratically. This in turn has led to the spread of blights and disease. The lack of rain has been accompanied by another unprecedented phenomenon: wildfires. In March 2016, a fire raged for three days on the slopes of Mt Gamalama. Forest fires of this intensity are new to the islanders’ experience. The ongoing changes in the world’s climate have thus placed the people of Ternate once again on the leading edge of history: the trees that guided their first steps in the world are now dying before their eyes as they watch helplessly.

This is a tragic predicament, considering that Ternate’s volcanic environment created an especially intimate, sacralized relationship between the island’s ecology and its people, who have long seen themselves as custodians of their closely interconnected world. And of none of Ternate’s people is this more true than the descendants of the dynasty of sultans that has presided over the island since the fourteenth century. Some members of this dynasty still live on the island, and during my visit in 2016, I was able to interview one of them, a prince who is the son of the late ruler and the current occupant of the sultan’s palace.

We sat in a courtyard that faced Mt Gamalama, so it was inevitable that our conversation should touch upon the dying clove trees that I had seen on the volcano’s slopes. Like so many others on the island, the prince attributed the death of the trees to climate change—this was, for him, a deeply troubling matter since these trees had sustained his family’s fortunes for 700 years.

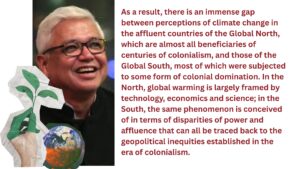

By the same token, attempts to impose limitations on the carbon emissions of poor countries are widely seen as a covert means of preserving the economic and geopolitical disparities of the last 200 years, since on a per capita basis the carbon emissions of the Global South are still a fraction of those of affluent countries.

These perceptions are mirrored in the West by the idea, now widely prevalent on the right, that the Global South is trying to deprive affluent nations of the hard-earned fruits of their success. In the US, the idea of imposing limits on America’s carbon emissions is also perceived by many as an infringement of national sovereignty, which is guaranteed ultimately y the country’s overwhelming military dominance.

In short, nationalism, military power and geopolitical disparities are essential to the dynamics that have repeatedly stymied efforts to reach a global agreement on rapid decarbonization. In that sense it could be said that conflict and national rivalries are fundamental drivers of climate change. Yet these issues are rarely discussed in conferences on global arming, which have come to be focused instead on technocratic and conomistic ‘solutions’ of various kinds. It is no coincidence that the literature on climate change, which is overwhelmingly produced by Western universities and think tanks, is also mainly centred on technical and economic issues.

In the South, issues like violence, race and geopolitical power are implicit in the perceptions of people like the clove farmers of Ternate. In the North, which is essentially secure in its position atop the global pyramid, these issues are rarely discussed, and climate change is generally treated as a problem of governance that can be resolved through processes of negotiation within multilateral institutions like the UN. But there is a very significant contradiction here. Multilateral institutions are mandated to operate on the assumptions that all nations and peoples are equal, and that wealth and welfare should be justly distributed between nations. Geopolitics, on the other hand, is founded on a completely different set of notions. It is not intended to bring about equality and justice, but rather the opposite. It is explicitly about maintaining a structure of dominance—or, in other words, inequality.

The dissonance between these two spheres—that of multilateral global governance on the one hand and geopolitical power on the other—is so great as to be almost irreconcilable. While the structures of global governance produce seemingly endless streams of ‘solutions’ and treaties, the repeated breakdown of international negotiations points to a different, largely hidden, reality. This unacknowledged dynamic was once summed up by a Singaporean journalist with the following words: ‘It is our will to power that will help us cope with one of the big driving forces of the future: climate change.’

In other words, global leaders may speak a certain language during international negotiations, but when we examine what they are doing it would seem that their actions are indeed driven by a will to power. That perhaps is why affluent nations were able to find only 10 billion USD for the fund to help countries that are exceptionally vulnerable, but had no difficulty in increasing their defence spending by 1 trillion USD. This suggests that contrary to what global leaders may say publicly, many of them are actually preparing for a future of intensified conflict.

One element of this challenge that provides some encouragement is that the aspirations of the middle classes of the Global South are essentially mimetic. That is to say when an Indian or Indonesian says, ‘Now it’s our turn’, what they are really saying is, ‘I will not be wealthy or content until I have what the Other has.’ It follows from this that if the supposedly wealthy Others were to change their ways and adopt substantially different lifestyles, then this could have a significant impact on aspirations across the World.

In this regard, the emphasis that Fridays for Future has placed on finding new ways to live is of vital importance. And the fact that their message has resonated so widely, even in the Global South, is a rare cause for encouragement.

Reproduced by Centre for Financial Accountability from Wild Fictions: Essays by Amitav Ghosh, published by HarperCollins India and with permission from University of Chicago Press, United States of America and Hodder and Stoughton, United Kingdom through PLSClear and Harper Collins India

A special thanks to Amitav Ghosh for allowing us to republish this segment.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram and WhatsApp. Click here to join our Telegram channel and click here to join our WhatsApp channeland stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.