Soumya Dutta traveled to Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, to participate in the 27th Conference of Parties (COP-27) of the UNFCCC.

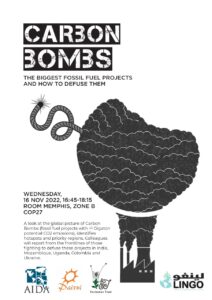

Along with participating in a host of meetings & public protests and speaking with journalists and activists present there, he also spoke in two important meetings- on False solutions and Global Carbon Bombs. Here he charts the most important takeaways from COP-27.

A positive outcome first: a decision on the loss and damage fund

- There was one positive outcome or initial gain for developing countries. As we all know, both

economic and other forms of losses and damages due to climate change impacts are accelerating across the world (but more so in poorer countries) and are now irreversible on a multi-decadal time scale. The “developing” and “poorer” countries were demanding for decades that a “Loss and Damage Fund” be set up, and “developed” or “rich countries” contribute to it so that poor, suffering countries can get some financial assistance for recovery. This is partly in keeping with the climate justice perspective, as the rich consuming countries have contributed overwhelmingly to creating this crisis, whereas the poor countries are suffering the most, though they have contributed little to the accumulated greenhouse gases (GHGs) that are causing these impacts.

economic and other forms of losses and damages due to climate change impacts are accelerating across the world (but more so in poorer countries) and are now irreversible on a multi-decadal time scale. The “developing” and “poorer” countries were demanding for decades that a “Loss and Damage Fund” be set up, and “developed” or “rich countries” contribute to it so that poor, suffering countries can get some financial assistance for recovery. This is partly in keeping with the climate justice perspective, as the rich consuming countries have contributed overwhelmingly to creating this crisis, whereas the poor countries are suffering the most, though they have contributed little to the accumulated greenhouse gases (GHGs) that are causing these impacts.

- Please be aware that this Loss and Damage Fund is distinct from the already established and agreed-upon “Climate Finance” of US$ 100 billion per year agreed in Cancun at COP-16 in 2010 and formalised in Paris in 2015, to be implemented beginning in 2020. It’s another matter that even this meagre amount of US $100 billion per year has not been given in full. Though the rich, developed, and Annex I countries are claiming that they are providing anything between $78 and $80 billion per year in climate finance to poor, developing countries, as of 2019, these are full of crafty miscalculations and inclusions. Many loans and “leveraged finances,” including interest-bearing private finances, are wrongly included in their figures. Independent civil society analysis shows that the real, verifiable climate finance to poor countries has been to the tune of USD 29–30 billion per year from 2019—about 30% of the promised figure. In this analysis, only grants and well-below-market-rate loans were accounted for, and rightly so. Commercial-rate loans cannot be considered climate finance.

- Not to forget, the US$100 billion a year is peanuts in comparison to the real losses and damages happening now; for example, this year’s devastating Pakistan floods alone have been assessed at roughly US$30 billion in losses and damages. According to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), developing countries require a minimum of USD 140 billion per year for adaptation alone, and this figure is expected to rise.The rough estimates for a comprehensive climate and biodiversity response range from USD 4,000 to 8,000 billion until 2050, or the next 28 years.

- For over 20 years, rich countries like the US, EU, Australia, etc. have stubbornly refused to accept the L&D Fund demands, thus effectively negating their historical responsibility for creating the climate change crisis. After some bitter negotiations by poorer countries and enormous pressure from global climate justice movements, the decision to establish a “Loss and Damage Fund” was finally accepted and incorporated into the official text.It’s still an empty fund; the modalities, etc., will be worked out only over the next 1-2 years. But still, it’s a victory for climate justice.

However, this gain is insufficient to compensate for the other setbacks in the negotiations (described below), which will accelerate these losses.

- The extremely important demand to phase out or phase down (in a short time scale) all fossil fuels (coal, petroleum, and natural gas) that are causing the GHG buildup, surprisingly pushed by the Indian delegation this time and supported by the large grouping G77+China and others, was shot down by rich countries. This should have been the first priority under the Mitigation Work Program. Pure self-interest over global catastrophe possibilities prevented any concrete proposal towards this—their economies are still highly oil and gas dependent. Unsurprisingly, Saudi Arabia played a major role in scuttling any mention of oil (petroleum) and natural gas, even going so far (and ridiculously outrageously) as to say that “since the negotiations are about emissions, energy should not be mentioned”! The fact remains that, facing gas supply shortages due to the Russia-Ukraine war, most developed countries have pumped up their own oil and gas production, while some like Germany have also increased coal power production. This was accomplished despite all governments and “parties” reiterating their commitment to the 1.5 C red line! How that will be adhered to is not clear, barring some miracle!

- This is back to the Glasgow COP-26 decision last year, when the reference to “phasing out coal,” proposed by rich countries as well as small island nations and others, was scuttled by China and India mainly (as our energy systems are overwhelmingly dependent on coal). So the official text this year, the “Sharm El Sheikh Implementation Plan,” does not make any mention of phasing out all fossil fuels, not even all coal, the most emissions-intensive fossil fuel. Instead, the word “unabated” was introduced in the text before “coal,” effectively saying that “unabated coal” should be phased out. This opens up risky and untested proposals of carbon capture and storage (CCS and CCSU) and others through multiple avenues, with possible additional impacts on communities and eco-systems where these CCS and CCUS programmes are likely to be implemented.

- Also introduced was the phrase “promoting low-emission energy sources,” which is another way of pushing natural gas (which has roughly half the CO2 emissions per unit of energy produced in comparison with coal)This ignores the fact that natural gas IS a fossil fuel that contributes significantly to the climate change crisis.nd natural gas-derived hydrogen, etc. This overlooks the fact that natural gas IS a fossil fuel that significantly contributes to the climate change crisis.Simultaneously, both developed-country governments and cash-strapped African governments are urging massive investments in natural gas exploration and production in promising African areas. The African and global climate justice movements are up in arms against this, with the slogan “don’t gas Africa,” but the governments are pushing hard. With the dreaded “Methane Bomb” looming on the horizon, the likely “fugitive emissions” from renewed gas explorations and productions are sure to push the Earth to Tipping Points of accelerated warming.

- Please note that even with the somewhat improved mitigation targets (over the Paris NDCs) submitted at the Glasgow summit last year, the Earth is on course to warm by at least 2.5 °C from its pre-industrial average by the turn of this century. According to the latest 6th Assessment Report series of the IPCC (released between October 2021 and April 2022), the Earth is on course to reach and breach the first climate red line of 1.5°C warming over pre-industrial levels in the decade of 2030-2040, which is really not that far. Increased exploration and production of fossil fuels will only hasten the march towards climate chaos.

- These facts leave hardly any time for global-scale changes to our entire energy systems and economies. And the IPCC reports are clear: to have even a 50% chance of remaining within 1.5°C, the world’s economies have to reach peak emissions no later than 2025 and reduce total global emissions (which stood at over 37 billion metric tonnes of CO2 in 2019) by at least 45% by the year 2030. Instead, emissions have started rising again after a COVID-forced dip in 2020. an emergency call by a scientific body such as the IPCC (as well as the WMO and many others) that has been completely ignored by the “COP-27 parties.” The “parties” to COP-27 are the governments that have ratified the UNFCCC.

- The official aim of the Mitigation Work Programis fast-paced emission cuts before 2030, and this needs lots of finances to be provided to the developing countries, as well as massive investments in the developed countries themselves.Unfortunately, developed countries refused to adopt new targets at COP-27, were unwilling to provide additional assistance to poor countries, and even attempted to implement a “sector-based emission reduction target system,” which would have placed a greater burden of mitigation on poor developing countries.

As a result of actual changes in many Earth systems, such as changing South Asian monsoon patterns, massive unseasonal fires, long-drawn heat waves, unprecedented flooding, and so on. Adaptation to these changes becomes extremely important for affected and vulnerable communities all across the country. The parties at COP-27 finally agreed on establishing a framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA) through the Glasgow Sharm El Sheikh Work Program (GlaSS), but the actual consideration and possible adoption of this is to be taken up at COP-28, next November or December in Dubai. Countries like the USA and Switzerland put up some roadblocks even to this, but finally this small gain was pushed through. Despite this GGA being established, there is no commitment or even clarity about where the financing for this will come from or through which modalities, thus rendering this a dead duck as of now.

Encourage the use of numerous erroneous solutions: Just as the COP-27 convened, the Advisory Committee on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement (articles 6.2 and 6.4 refer to market mechanisms for mitigation, which are a sham as many of our studies have revealed) “approved” the dangerous “Ocean Carbon Dioxide Removal” method of ocean fertilisation for carbon markets.

This is despite the fact that, at scale, pilot projects of ocean fertilisation (led jointly by Indian and German research institutions in 2009) have failed to show significant positive sequestration. Ocean CDR, if supported by large amounts of market capital, will enable risky, large-scale experimentation in our oceans and seas. The overall push for “offsetting,” carbon markets for mitigation, etc. continued though, with increased focus on shifting away from actual emissions reduction to market-based mechanisms that do not actually reduce, as shown over the last decade and more.

After huge protests and a strong stand against this taken by some countries, the proposed “approval” for Ocean CDR was sent back to the Advisory Committee with a 2-year timeframe to do better groundwork. The danger still remains.

The COP-27 happened under the shadow of massive human rights violations, the brutal suppression of all dissenting voices, and curtailment of rights for even the civil society participants in the COP-27 (the “observers” in UNFCCC terms). We were clearly told that we could not name any country or company in any of our presentations! Outside the venue, protests and even gatherings were strictly prohibited. The searching and questioning of many civil society activists happened on both inward and outward journeys. The references to human rights, indigenous people’s rights, etc. were omitted from some texts.

The COP-27 happened under the shadow of massive human rights violations, the brutal suppression of all dissenting voices, and curtailment of rights for even the civil society participants in the COP-27 (the “observers” in UNFCCC terms). We were clearly told that we could not name any country or company in any of our presentations! Outside the venue, protests and even gatherings were strictly prohibited. The searching and questioning of many civil society activists happened on both inward and outward journeys. The references to human rights, indigenous people’s rights, etc. were omitted from some texts.

Despite these, civil society found ways to counter and respond to the massive human rights violations by the dictatorial Egyptian government. Finally, on the 17th of November, the People’s Plenary reverberated with calls like “Free Ala, Free Them All.” This was defying the unjust and authoritarian restrictions that they tried to impose.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram. Click here to join our Telegram channel and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.