- In the last four years since Amaravati was conceived, the government has successfully aggregated 34,000 acres of land from almost 28,000 farmers.

- According to agriculture experts, the area between Guntur and Vijayawada, which been earmarked for Amaravati, is one of the most fertile belts of the state.

- Former agriculture Minister Vadde Sobhanadreeswara Rao said the government should have a decentralized approach towards the development of the state of Andhra Pradesh.

Amaravati is a city framed in constant motion — or shall we say construction? Large swathes of barren land are tossed over and trampled by bulldozers and trucks that snake afar, in preparation for a massive building frenzy. Workers are hard at work, prompted into continual action by orders barked by contractors. It is rugged, dusty terrain now, but the promise of a succession of modern buildings has attracted a gaggle of buses packed with visitors.

Amaravati is Andhra Pradesh’s new capital city, coming up on the banks of the river Krishna. The need for a new capital was prompted by the decision of the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government to carve the state into two — Andhra and Telangana — in 2014. Hyderabad, the existing capital, was to be shared between them for 10 years after which Telangana would get sole rights. A year later, the foundation stone for Amaravati was laid.

The capital holds the promise of grandeur. Spread over 217 square kilometer, Rs 48,000 crore will be sunk into just the first phase. The master plan has been designed by the Singapore government and several international consultants have also poured their insights into the development.

Amaravati is poised to be not just a smart city but also a happy one. Nine thematic districts — based on sports, government, finance, tourism, health, knowledge, electronics, justice and media — each self-contained with school, hospitals retails and offices will be built on sustainable green building techniques. Water canals will run through the city. Space has been devoted for evehicles and cycling tracks. The aim — to be one of the top three happy cities of the world. Also in the works is a start-up area, all of which sprout on 1,691 acres in three phases.

That’s not all. With a raft of underground utilities, the state government plans to make the city dig-free for at least 100 years.

N Chandrababu Naidu, chief minister, Andhra Pradesh is optimistic about the progress of the city. “We are going in a fast-track manner,” he says.

But fulfilling ambitions of this magnitude needs money. Lots. So far the government has managed to raise Rs 2,000 crore through municipal bonds. Talks are on with World Bank and HUDCO for more debt financing.

Capital remains the biggest obstacle to Naidu’s dream capital. Promised funding from the central government is no longer available. Funding has been the bone of contention between Naidu and the centre; so much so that Naidu’s Telugu Desam Party (TDP) parted ways with the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) coalition of parties.

A mock-up of the capital.

But S Shan Mohan, chief executive officer, Amravati Smart City, remains sanguine. “While we were expecting some support from the centre, we had a parallel plan where we tie up most of our funding using multilateral agencies and private banks. Our entire housing project is based on private bank tie-ups,” he said.

How The Government Got Land

Money may be a problem, but the Andhra Pradesh government has at least one thing going for it — land. In the last four years since the city was conceived, the government has successfully aggregated 34,000 acres of land from almost 28,000 farmers.

This makes it one of the largest land pooling schemes in the world. Currently, 52,000 acres are in the state government’s possession.

Tardy land acquisition has been the bane of development projects in India. Most states find it extremely difficult to acquire land for several of their developmental projects due to the protective clauses of the Land Acquisition Act of 2013. How then did Andhra Pradesh succeed?

Instead of trying to buy land, the government “pooled” the land from farmers. Farmers voluntarily gave their land to the government in return of residential and commercial plots. Farmers will also get annuity for the next 10 years depending on the size of their land holdings. They were also persuaded by potential social benefits such as health and education and livelihood transition.

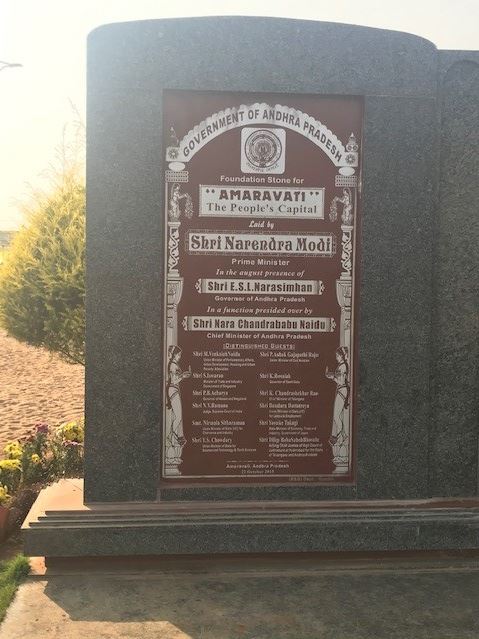

The foundation stone of Amaravati laid by Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

Land pooling has proved to be faster and more efficient that the tradition land acquisition method, which is time consuming as well as complicated. Land pooling is bereft of disputes of compensation associated with traditional land acquisition methods; the financial burden on the government is also lessened.

Andhra Pradesh is hardly the first state in India to pursue land pooling. Several states have managed to secure land in this manner, notably Uttar Pradesh.

But Andhra Pradesh is arguably the fastest to do so. More than 33,599 acres have been pooled from 27,365 farmers. That translates to 90 percent of the land required for the development of Amaravati.

Naidu is grateful. “Nowhere in a democratic country in the world have farmers voluntarily given 33,000 acre of land,” he said.

But there are a significant number of landless farmers who used to work as labourers who have lost their livelihood after the lands were pooled. The state government is providing them with annuity and skill development programmes.

There are also worries, due to the souring of relationship between the state and central government, that the fortunes of farmers who have volunteered to give their land will be impacted.

Some of the farmers CNBC-TV18 spoke to said they have faith in Naidu.

“We have given the land because of our trust on the CM. We are confident that CM manage to bring money to build this capital city,” says Polu Kalyan Chakravarthy.

The Other Side

Not all farmers are as happy as Chakravarthy. Two of the 29 villages that the state government has identified for the scheme are yet to give their land.

According to agriculture experts, the area between Guntur and Vijayawada, which been earmarked for Amaravati, is one of the most fertile belts of the state.

An agriculture expert said taking away fertile land will not just have environmental ramifications but will also hamper the food security of the state. “Moreover, the transition of farmers to non-agricultural activities is not a cakewalk. Without proper training and employment opportunities it is going to be extremely difficult. It is quite clear that the government is acting like a realtor,” he said on the condition of anonymity.

The farmers opposed to land pooling agree. In a telephonic interview, a farmer who owns significant amount of land in one of the villages said around 1,600 farmers have resisted the land pooling efforts of the government.

Another farmer said he is worried what will happen to his land when the government changes. “Of the thousands of farmers who have given their land, how many of them know English and our educated enough to read the fine print of the scheme? Till now we can only see 3D videos of the project and crores of rupees have been just wasted on marketing.”

Both of them spoke on the condition of anonymity.

A report published by Centre for Financial Accountability (CFA) in 2017, notes that “the stretch along the Krishna on which Amaravati will be built is a highly fertile floodplain – or a catchment area that replenishes itself naturally during rainfall and flooding, maintaining the water level of the soil, as well as the flow and ecology of the river, by continuously absorbing and discharging water”. Constructing on a floodplain would destroy that natural system of absorption and discharge and severely raise the risk of flash flooding, according to the report.

Members of an outfit called National Alliance of People’s Movement have also been raising the issues of discrimination towards Dalit farmers, small and marginal cultivators who have lost their land and source of livelihood due to Amaravati.

Many others have also questioned the need to have a new capital in the first place. Former agriculture Minister Vadde Sobhanadreeswara Rao said the government should have a decentralized approach towards the development of the state of Andhra Pradesh instead of just focusing on a capital city.

The article, first published by the CNBCTV18.com, can be accessed here.