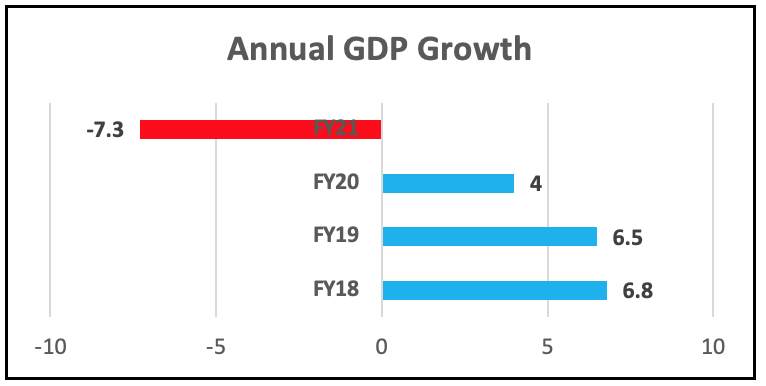

If the GDP growth rate is an indication of where our formal economy is, then there’s a lot to worry about. It fell to -7.3% in FY21, from the low of 4.2% in FY20. Unless the IT cells come out with some convoluted explanation to show -7.3% higher than 4.2% (as they did about the petrol prices), the outlook remains bad. In the first quarter of FY21, the contraction was -24.4%, in the second, -7.3%, in the third 0.4% and in the last, it recovered to 1.6%, resulting in annual growth of -7.3%.

This is the worst GDP growth rate in independent India and the first contraction in more than 4 decades. In 1979-80, India’s GDP contracted by -5.2% owing to the second global oil shock following the Iranian Revolution. Before that, the economy of British India contracted by 10.5% in 1918 when the second wave of the influenza pandemic killed more than a crore Indians and crippled the economic activity in the country.

Some may be in a mood to give a long rope to the government with the idea that the pandemic, or the “Act of God” as our Finance Minister calls it, after all, has led to a shakedown of the economy across the globe. But then the economy has been on a downslide well before the pandemic knocked on our doors. The government’s reckless decision to demonetize 86% of the currency at 4 hours notice in 2016 triggered this slide. Tremors of that, and the poorly designed and badly implemented Goods and Services Tax (GST), broke the backbone of the informal sector and small businesses, the largest contributor to the economy and employer of 80-90% of the workforce. Battered by these moves, our GDP figures have seen a secular deceleration since the third quarter of 2016-17 falling from over 8% in FY17 to about 4% in FY20. It fell to a 42 year low (in terms of nominal GDP) in January 2020, just before Covid-19 hit the country. The pandemic only accelerated it.

Though both the State of Economy (SoE) report (of RBI) and the Month Economy Report (MER) try their best to forecast a “not so bad” picture in the coming days, it cannot be denied that given the second wave went well into the rural hinterland this time, recovery is going to be more delayed and difficult. Soumya Kanti Ghosh, the Group Chief Economic Adviser, SBI, echoes the same saying, “our analysis shows a disproportionately larger impact on the economy this time and given that rural is not as resilient as urban, the pick up in pent-up demand is unlikely to make a large difference in FY22 GDP estimates, and hence it could only be a modest pickup.” Without increased state expenditure, which is an anathema for our neoliberal overlords, the “picture of economic resilience is an illusion”, says CP Chandrasekhar.

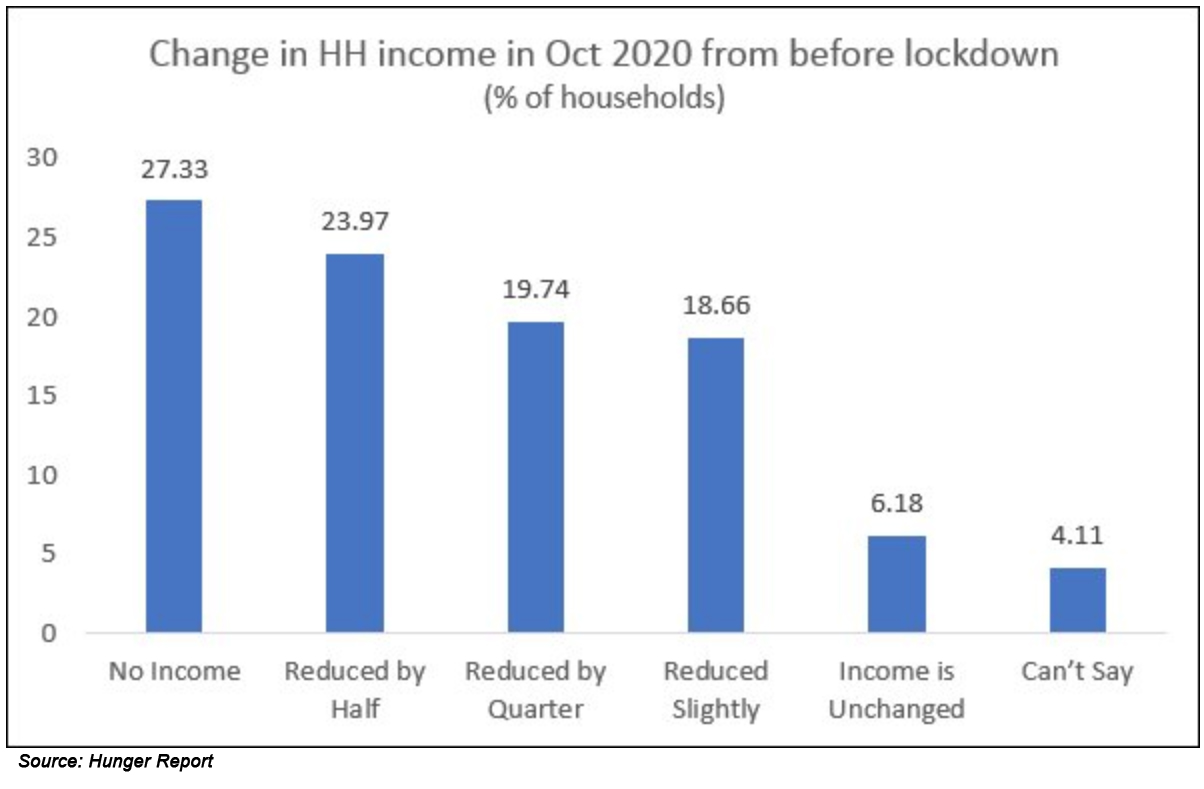

How has the nosedive of our economy impacted the common people? There’s a pandemic of hunger and indebtedness raging across much of India. Household incomes have drastically reduced resulting in a dramatic increase in hunger. The Hunger Report says, “…the levels of hunger and food insecurity remained high with little hope of the situation improving without measures specifically aimed at providing employment opportunities as well as food support. Families are using different coping mechanisms – we have seen children being withdrawn from schools and sent to work, assets and jewellery being sold, money being borrowed to buy food, massive reductions in the quantity and quality of food consumed.”

Joblessness has broken the glass ceiling! While the government has been high on rhetoric, the unemployment figures, according to the Statistics Ministry in FY18 stood at 6.1% – a 45 year high. This again was a record achieved by the government well before the pandemic.

Things haven’t gone north since then. In a recent interview Mahesh Vyas, CEO of Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, said the unemployment rate  in the third week of May 2021 was 14.7%, more than double of FY18. This is more worrisome given that these are figures even amid a falling labour force participation rate.

in the third week of May 2021 was 14.7%, more than double of FY18. This is more worrisome given that these are figures even amid a falling labour force participation rate.

According to latest reports, at least 1.5 crore workers lost their jobs in May. This is only for the formal sector and on top of the jobs already lost in FY21. Numbers for the informal sector would be many folds because of the way the lockdowns impact the respective sectors. This reminds one of the song by Gulzar that has the protagonists informing us that they have wasted their time in completing bachelor and masters degrees because they don’t have any employment opportunities, that there is “bhashan everyday but no ration”, and that “aapki dua se sab theek-thaak hai” (their version of “sab changa sii”)!

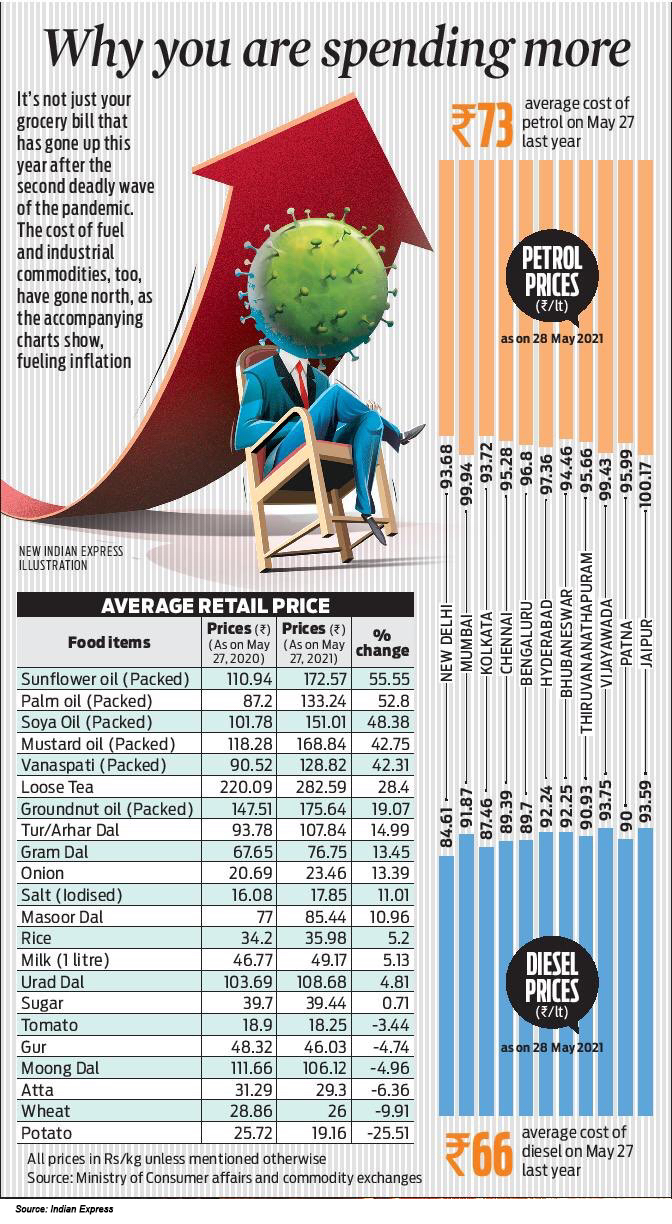

While jobs are scarce, income drastically reduced, hunger is a reality knocking at the door, prices of essential commodities are skyrocketing, in some cases nearly 50% within a year. Relying on higher taxes on fuel to generate revenue in an economy that is on its knees, it is estimated that the government collected an additional Rs 1.8 lakh crore in 2020-21 through the hike in excise duty on petrol and diesel. In May 2021 alone, the prices were increased 17 times!! That has a cascading effect on the prices of essential goods, as seen in the chart.

While jobs are scarce, income drastically reduced, hunger is a reality knocking at the door, prices of essential commodities are skyrocketing, in some cases nearly 50% within a year. Relying on higher taxes on fuel to generate revenue in an economy that is on its knees, it is estimated that the government collected an additional Rs 1.8 lakh crore in 2020-21 through the hike in excise duty on petrol and diesel. In May 2021 alone, the prices were increased 17 times!! That has a cascading effect on the prices of essential goods, as seen in the chart.

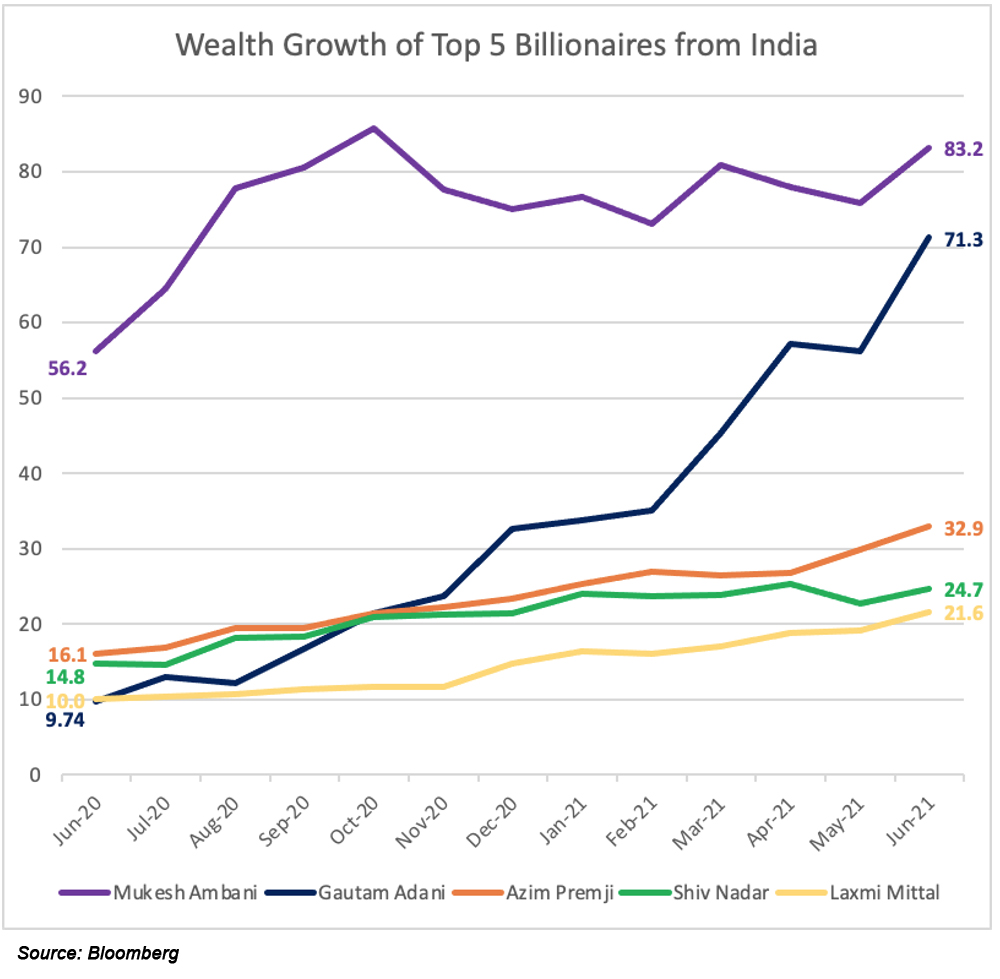

The Aam Aadmi has been reeling under the impacts of a crumbled economy. Not the Khaas Aadmi! According to Bloomberg Billionaires Index, Gautam Adani’s total fortune stood at $71 billion in early June 2021. A year back, it was $9.75 billion, a growth of 728% in a year. That’s $61.6 billion in one year, or $169 million or Rs. 1,217 crores per day. It is reported that Adani’s wealth accumulation this year was more than the combined wealth addition of $24.5 billion by 19 other Indian billionaires together.

Some facts from Oxfam’s Wealth Inequality Report 2020 put these numbers in context:

- The top 1% of Indians hold more than 4 times the amount of wealth held by 953 million people (or the bottom 70% of the population).

- It would take a female domestic worker 22,277 years to earn what a top CEO of a Tech company makes in one year. With earnings pegged at INR 106 per second, the CEO would make more in 10 minutes than what the domestic worker would make in one year.

- Women and girls put in 3.26 billion hours of unpaid care work each and every day—a contribution to the Indian economy of at least INR 19 lakh crore a year; which is 20 times the entire education budget of India in 2019 (INR 93,000 crores)

- Direct public investments in the care economy of 2% of GDP would potentially create 11 million new jobs. This would make up for the 11 million jobs lost in 2018.

In another report, Oxfam says, “Getting the richest one percent to pay just 0.5 percent extra tax on their wealth over the next 10 years would equal the investment needed to create 117 million jobs in sectors such as elderly and childcare, education and health.” They were talking about the world’s richest, but the Indian scenario is not different. Not only that there’s no move to tax the richest in India, but it has also consistently been reducing the corporate tax rate. It was 34.61% between FY15 and FY17, it fell to 30% in FY18, again cut in FY19 to 25.71% and FY21 to 22%.

While the -7.3% growth is having a devastating impact on the economy, one needs to recognize that this is about the formal economy, not the informal economy. During the Qr1 contraction of 24.4%, senior economist Prof. Arun Kumar argued that the real contraction would be 40%, considering the informal sector as well. Earlier this year, in an interview he said the annual growth would be -25%. He said, “India’s economic growth is not recovering as fast as the government is showing because the unorganised sector has not started recovering and some major components of the services sector have not recovered. My analysis shows that the rate of growth will be (-)25 per cent in the current financial year because during the lockdown (during April-May), only essential production was taking place and even in agriculture, there was no growth.”

In March this year, Minister of State for Finance Anurag Thakur said that there are green shoots visible in various sectors of the economy and the country is already looking at a V-shaped recovery. One is not sure about green shoots, but the V-shaped recovery is already taking place and is visible. The GDP growth rate is the story of that V-shaped recovery. In this, the downward handle of the letter ‘V’ is reserved for common people and the upward handle is for the wealthiest 1%.

Om Prakash & Anirban Bhattacharya contributed to this analysis.