Introduction

When the Modi government came to power in 2014, two urban programmes – Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) and Rajiv Awas Yojana (RAY) – of the union government were being implemented in Karnataka and other states. The new BJP government wound up these two programmes and rolled out three new flagship programmes – Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojane (PMAY), Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation (AMRUT) and Smart City Mission (SCM). The last one of these programmes – the Smart City Mission – was launched with a lot of fanfare, and an investment of RS 1000 crores was promised for 100 selected Smart Cities. Before this, the concept of Smart City was being discussed by businesses, academic and technology circles but with the launch of the Smart City Mission in June 2015, the idea of Smart City became a topic of public discussion. With the hype surrounding the Smart City Mission, people’s expectations also increased. Since the concept of Smart City was never defined very concretely, everyone interpreted the concept based on their own expectations. Where does the Smart City Mission stand in Karnataka after 6 years of launch of the Smart City Mission? This article analyzes the concept and implementation of Smart City Mission from a social justice perspective, by taking an in-depth look at the Smart City Mission in Tumakuru.

The Selection Process

The Smart City Mission introduced some new features in terms of how urban development programmes are implemented in India. Usually, the cities included in the programmes are selected based on some criteria or the decision is left to the state governments. But in Smart City Mission, a two-stage competitive process for selection was introduced. Each state was allowed only a fixed number of cities based on the urban population in the state and the number of cities/towns in the state. Karnataka was allotted 6 cities. At Stage I of the selection process, cities within the state were to compete with each other and based on their past performance, the number of cities allotted were to be selected for Stage 2 of the process. In Karnataka, all the 11 City Corporations participated in Stage 1, out of which Belagavi, Davangere, Hubballi-Dharwad, Mangaluru, Shivamogga and Tumakuru were selected for Stage 2. For Stage 2, these cities were given a sum of Rs 2 crores to prepare a Smart City Proposal by engaging private consultants. The Ministry of Urban Development (MoUD) selected those cities whose proposals were found to be adequate and the unselected cities were asked to revise and resubmit the proposals for the next round of Stage 2 selection. In Karnataka, Davangere and Belagavi were selected in first round itself (2016), Hubli-Dharwad, Tumakuru, Mangalore and Shivamogga were selected in second round (2016) and Bengaluru city which was added to the Smart City list based on special request from Karnataka, was selected in Round 3 (2017).

Apart from the selection process, another change introduced by Smart City Mission was in terms of the approval process for centrally sponsored scheme. Unlike JNNURM and RAY, instead of project-by-project approval, under the Smart City Mission, the Union government would give one-time approval to the Smart City Proposal, and decision regarding further changes were left to the State-level High Powered Steering Committee (HPSC) constituted for the Mission. Additionally, the implementation of the selected Proposal was to be done not by government departments or agencies but by a special purpose vehicle which was a public limited company with 50:50 ownership divided between state government and the city corporation. The Guidelines of the Mission required substantial powers of the City Corporation to be delegated to the SPV through amendments to the Municipal Corporation Acts. The SPVs were envisioned as the main decision-making body with respect to the implementation of the projects included in the Smart City Proposal.

The Smart City Proposal was to be formulated by the cities after extensive consultation with ‘citizens’. The Guidelines mention ‘city’ and ‘citizens’ as homogeneous concepts ignoring the unequal power relations within the city and between citizens and groups based on caste, class and gender. Unlike JNNURM where special components were provided for the urban deprived communities, in Smart City Mission no such special measure has been taken to ensure the needs and concerns of urban deprived communities is included in the Smart City Proposal.

The Smart City Proposals to be submitted by the selected cities were required to have two components: Area-based Development (ABD) and Pan-city component. The concept of area-based development was also a new introduction to urban development programmes. Instead of focusing public spending on the whole city, the selected cities were required to select a specific area for development on which most of the investments would be concentrated. The city could choose between city improvement (retrofitting of an existing area), city redevelopment (redevelopment of existing area) or city extension (development of a new area at the periphery of the city) under the area-based development. As part of the pan-city development, the city was required to propose IT-based Smart Solutions to existing infrastructure for the whole city so that even residents of areas not-included in the area-based development also feel connected to the Mission. These projects included in the Smart City Proposal could be financed through SCM funding, PPP funding or through convergence with other Union/State government schemes.

Progress of Smart City Mission in Karnataka

In Karnataka, cities of Belagavi and Davangere were selected in 2016 and have completed the 5-year duration of the mission. The pace of the Mission has been slow in both cities with 55.86% and 29.63% projects being completed in Belagavi and Davangere respectively. In terms of project cost, the completion rates (37.79 and 9.08 respectively) are much slower indicating while smaller projects have been completed the bigger projects remain completed. For Hubballi-Dharwad, Mangaluru, Shivamogga and Tumakuru which would complete 5-years by March 2022, the completion rates in terms of number of projects are: 27.40, 35.71, 46.59 and 53.57 respectively. Thus only Tumakuru has be able to complete half of the proposed projects after 5 years of the Mission. In terms of project cost, the completion rates are much worse: Hubballi-Dharwad (15.33), Mangaluru (4.91), Shivamogga (5.58) and Tumakuru (12.60). For Bengaluru which was selected in 2017 and has completed 3 years of implementation the completion rate in terms of number of projects is 9.30% and in terms of project cost is 0.56%! Most cities in Karnataka are most likely going to miss the Mission deadline.

Smart City Mission in Tumakuru

To begin with the Smart City Proposal for Tumakuru claims that for the preparation of the Proposal, 1,75,000 citizen engagements! For an estimated population of 3,05,821 persons, this implies that every second person was engaged with through the consultation process. But our interviews with members of urban deprived communities in Tumakuru including Pourakarmikas, UGD workers, street-vendors and leaders and activists of organizations working across various low-income settlements suggest that most of the members of the marginalized communities were not involved in any such survey or outreach programme. For example, Mr. Kadarappa, a leader of the Pourakarmika Sangha (Sanitation Workers Union) made the following observation:-

We all work for the Corporation and we keep visiting the offices almost every week, but we were never called for any consultation regarding Smart City. The first time we came to know about Smart City was when Mr. T Bhoobalan, the Corporation Commissioner was given additional charge as MD of TSCL (the SPV).

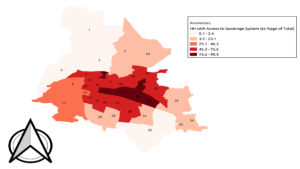

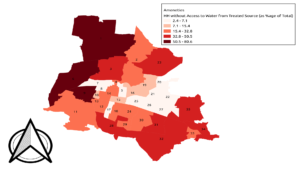

One of the reasons for exclusion of the marginalized sections from the engagement process was because most of the process was carried out through online modes (corporation website, emails, Facebook, mygov.in website, twitter, youtube etc.) and were largely one-way communications informing people of selection of Tumakuru for Stage 2 of selection process. The process of arriving at the Mission statement for Tumakuru was limited to university students and professors. The winning vision statement – KIND (Knowledge and Industrial New Destination) City – was suggested by a University Head. Subsequently, there were two significant rounds of citizen engagement initiatives. In Round 1, surveys and meetings were conducted focusing on soliciting citizens’ opinion on their level (dis)satisfaction with basic (core) services. Only 3% of the respondents in this Round were residents of ‘slums’ while rest of the respondents were students, industry associations, religious organizations, residents welfare associations etc. The limited participation of urban deprived communities created a middle-class bias in the responses which got reflected in the issues identified during Round 1 of the citizen engagement process. Irregular power supply was identified as the biggest problem facing the city by the largest percentage of respondents, followed by solid waste collection, drainage, pedestrian facilities and parking facilities. Issues like affordable housing, health infrastructure, street vending zones, auto-rickshaw stands didn’t even figure in the list of priorities. Nevertheless, dis-satisfaction with basic services and infrastructure came out very clearly from the feedback, and although not all communities had equal access to these services in the city, improvement in the existing level and quality of services was an aspiration shared across all social groups, and more so by those who had limited or no access to services like piped water supply, drainage, solid waste collection, public transport etc. Thus the feedback from the citizens, however skewed, would have suggested a strong focus on improvement of these basic services and associated infrastructure. In case, pan city improvement was not feasible owing to limited availability of funds, a social justice approach would have warranted a focus on those areas where such infrastructure was inadequate or non-existent. As the maps show, the core areas of the city fare much better in terms of access to services like water supply, sewerage system and drainage facilities, while the wards on the periphery have inadequate access to these services.

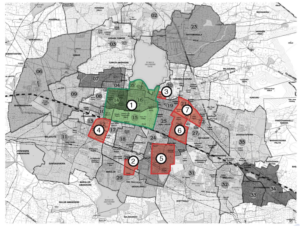

Yet, the seven clusters identified for Area-based Development (listed below and also shown on map) were all from the core area of the city.

- RETROFITTING

- Railway station area, Town Hall area, Bus station area, MG road as city center.

- REDEVELOPMENT (‘Slums’)

- Indira colony, Maralurudinne slums.

- NR colony slums.

- Shanthinagara slums.

- RETROFITTING (Residential)

- Jayanagar (E), Maruthinagar, Nrupathunga Extn, Siddarameshwara Extn, Manjunatha nagar, Gokula Extn.

- S S Puram, SIT Area

- Vidhya Nagar, Nrupathunga Ext 2.

Out of these clusters, three clusters -1, 4 and 5 -were selected based on the responses received and put to vote again, which yielded 1 an 5 as the final contenders. The option of redevelopment projects in ‘slums’ was quickly voted out of reckoning, and the eventual choice was between city core areas (1) and the residential cluster in Jayanagar and Maruthi Nagar (5). Eventually, at the third selection stage Cluster 1 (Railway station area, Town Hall area, Bus station area, MG road as city centre) received 77.63% of the votes and was selected based on just 1,101 votes, a majority of which were polled online.

The combined result of the exclusionary nature of the Citizen Engagement process in terms of non-participation of large sections of urban deprived communities in the city, the fact that redevelopment of identified slums (Cluster 3-5) was proposed as a standalone option, the misfit of standalone redevelopment of slums with the over-arching vision for the Smart City Mission, ensured that inclusion of these areas was a losing proposition right from the beginning.

Mr. A Narsimhamurthy, Karnataka Slum Janadolana while speaking at one of the workshops as part of Citizen Engagement, raised the issue of social justice and the need to prioritize the development needs of urban deprived communities but these concerns were not taken on-board. The final shape that the SCP took was born in a ‘Visioning Exercise’ conducted by urban experts like A Ravindra. The SCP submitted for Round 1 of the Stage 2 of City Challenge had included only Ward 5, 14, 15 and 16 (city core areas) and Amanikere lake area under area-based development. This proposal was rejected and Tumakuru was asked to revise its proposal.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram. Click here to join our Telegram channel and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.