Introduction

Promotional Image of Tinsukia Plastic Park. Picture courtesy: Advantage Assam/Twitter

Big money is set to fuel the making of more plastics in India. The production of phenolics in India began in 1947 and the first thermoplastics (polystyrene) were made in 1957 (PlastIndia, 2019). In 2018-19, the production of plastics in India was 170 lakh tons (PlastIndia, 2019). According to the same report, the industry size was INR 5.1 lakh crore with around 4,000 converting units in 2018-19. Over the years, plastic production has substantially increased. All these factors make it imperative to understand the complex structure and organisation of the plastics industry in India to assess the current status, and understand future projections and financing.

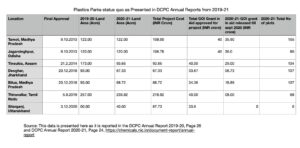

CFA, in its first article on the issue, outlined the process of plastics production and processing, and provided an insight into the structure of the Indian plastics industry. In 2013, the Department of Chemical and Petrochemicals (DCPC) introduced a ‘Scheme of Setting Up Plastic Parks’ with the objective of giving impetus to polymer production through a cluster development approach. 10 plastic parks have been granted final approval with Rs. 132.52 crores as grant-in-aid released for 7 Parks.

This article, the second in the series of two articles on the plastics industry, presents an overview of Plastic Parks and looks at the one in Assam to understand the interface of the plastic processing scheme, land and finance on the ground.

What are Plastic Parks?

According to the Scheme, state governments are responsible for coming up with projects for Plastic Parks, with the goal of generating employment, contributing to the economy by drawing upon cluster development and increasing the production and exports of plastic articles. The broad objectives of the Scheme emphasise India’s potential for attracting investments, plastics exports and environmentally sustainable growth. The need-based Plastic Parks with state of the art infrastructure are to consolidate and synergise the capacities of the domestic downstream plastic processing industry—some 30,000 micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the unorganised sector (DCPC, Annual report 2018-19). Under the scheme, the GOI provides a grant in aid to State Governments for meeting 50% of project costs and upto a maximum of Rs. 40 crore per Plastic Park.

Plastic Parks are industrial zones devoted to plastic enterprises and allied industries encompassing a range of companies required for the plastics processing community from material and machinery suppliers, plastics processing companies, plastic recycling companies including waste management systems where entrepreneurs might set up their units and benefit from common infrastructure and facilities such as tool room and technology support. Nearly all parks include some basic facilities of water, power, drainage and some common facilities that are necessary for a business hub. The Plastic Parks of Assam and Odisha offer tool room facilities. They also hint towards nearby availability of raw materials and highlight the presence of CIPET for training, skill up gradation and testing support. The two parks in Madhya Pradesh offer diverse packages of monetary incentives for MSME and large enterprises, and the plastic park in Odisha has the benefit of a ‘plastics product evaluation centre’ (PPEC) located in Paradeep for providing technical service to the plastic park. Some of the Plastic Parks provide subsidies for STPs (sewage treatment plants) and ETPs (effluent treatment plants)— infrastructures that are not specific to the plastics industry. Monetary incentives and tax reimbursements also vary with the Madhya Pradesh ones providing more monetary incentives in comparison with the other Plastic Parks. (1)

According to the sparse information available in CAG (Comptroller and Auditor General of India) reports, the Plastic Parks have yielded negligible profits and more consistently losses. Some of the Plastic Parks have come under the CAG scanner, surfacing financial irregularities such as the West Bengal Poly Park. The next section examines the union government’s financing of plastic parks.

Expenditure on Plastics Parks Scheme

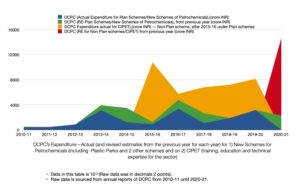

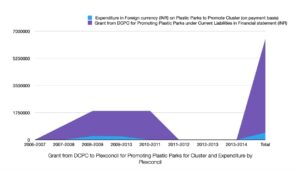

Expenditure on the ‘Scheme for Setting up Plastic Parks’ is combined with the expenditure on two other schemes (National Innovation Awards and Technology Upgradation centres), under the single head ‘New Schemes for Petrochemicals’ since 2010 in annual reports of the DCPC. The exact expenditure on the scheme and on each Plastic Park project and status of each project is not listed annually or in a single report. The DCPC gave grants to the Plexconcil (Plastics Export Promotion Council of India—the apex plastics export trade body funded by the GOI’s Ministry of Commerce and Industry), for advertising the Plastic Parks outside India between 2007 and 2012, a small fraction of which was utilised. (2)

The GOI’s grant to the states is contingent upon successful completion of project phases. So far, two plastic parks (Assam, Odisha) were given the second instalment and one park was sent the third (Tamot, Madhya Pradesh). Five plastic parks were given a final approval (Madhya Pradesh (Bilua), Tamil Nadu, Jharkhand, West Bengal, Uttarakhand). The DCPC reports tabulate the status of seven plastic parks from 2019-2021 and such a status update was not presented in the annual reports prior to 2019.

The table above from DCPC’s 2019-20 annual report suggests that six Parks have received atleast one instalment. Two parks received the second instalment (having utilised 60% of the first instalment). One park received the third instalment (having utilised the previous instalment and after allotting 25% of the plots). It is evident that no Plastic Park received the fourth instalment and we can infer that no Park has 50% of the units operational as yet according to the scheme guidelines for releasing funds for the plastic parks. The next section looks at changes in land area of Plastic Parks.

Land Fluctuations

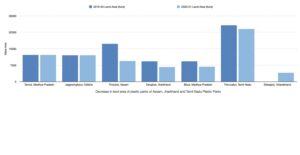

The land area of four parks (Tinsukia, Assam, Thiruvalluvar, Tamil Nadu, Deogarh, Jharkhand, Bilua, Madhya Pradesh) decreased from 2019-20 to 2020-21 while project costs and other heads remained the same, the reason for which is not yet known. Curiously a key suggestion that emerged for boosting the plastic parks was the need for acquiring more land. This step differs from the suggestions that followed from a review of the other major projects of the DCPC (The PCPIRs new draft policy of 2020 proposes decreasing land area).

Inside The Plastic Park at Gelapukhuri, Tinsukia, Assam

The Assam Industrial Development Corporation (AIDC) of the Government of Assam is the implementing agency for the plastic park at Tinsukia, Assam. The AIDC’s infrastructure projects in 2016-17 included the Plastic Park at Gelapukhuri, Tinsukia that was set up under the Plastic Parks scheme ‘to provide industrial infrastructure facilities to encourage entrepreneurs for setting up of plastic processing industries utilising the products of Brahmaputra Cracker and Polymer Limited (BCPL), Dibrugarh.’ The Tinsukia Plastic Park was one of the first four plastic parks to receive the final approval from the GOI in 2013-14 (DCPC Annual report 2014-15, page 56).

Two reasons for the speedy approvals for Assam’s plastic park could be availability of raw materials due to the presence of BCPL in the region and a prospective estimation of a future plastics market in North East India. Firstly, the plastic park could utilise the 200,000 tonnes per annum polymer produced at the BCPL. Secondly, the per capita consumption of plastic in Assam was only 1-2 Kg in comparison with the national average of 6-7 Kg in 2014. Tinsukia could produce finished products that can be sold in neighbouring markets of Myanmar, Bangladesh, Bhutan, among other regions in SouthEast Asia’. According to the KNN (2014) since the ‘plastic market is supply driven,’ the increase in production is likely to boost the north eastern plastics market.

According to the AIDC Annual Report for 2016-17, the total cost of the Plastic Park project at Tinsukia is Rs. 93.65 crores. Other sources report the project cost to be Rs. 250 crores (Advantage Assam). The park was expected to generate direct employment for 6,800 and indirect for another 9,700. The park was expected to accommodate 151 large, medium and small plastic processing industries (AIDC Annual Report for 2016-17). The following section examines financing of the park by the union and the state governments.

Financing the Plastic Park

The union government (through DCPC) has provided a grant in aid of Rs. 40 crores and the Government of Assam (Industries and Commerce Department) has contributed Rs. 53.65 crores. The Tinsukia Plastic Park received the first Instalment of Rs. 8 crore of grant in aid from the GOI in 2013-14 (DCPC Annual report 2014-15, page 56). The AIDC’s annual reports are only available online for the years 2012-13, 2013-14 and 2016-17. Despite the sanction of Rs. 8 crores from the GOI, there is no mention of a plastic park in AIDCs annual report for 2013-14.

According to analysis of DCPC annual reports, Assam was also the first plastic park to receive the second installment of Rs. 14 crore in 2015 (DCPC Annual Report 2015-16, page 27). (3)

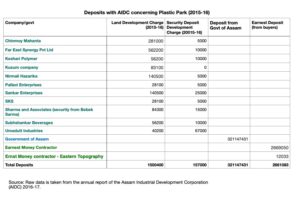

The Government of Assam deposited INR 32,11,47,431 in Accounts of the AIDC for the Plastic park in 2015-16 (AIDC, 2016-17, page 75). In addition, the AIDC received total deposits of land development charge (INR 15,00,400) and security deposit (INR 1,57,000) from around 11 companies. The total earnest money deposit (the deposit paid by a buyer to the seller, here the AIDC) for Plastic Park was INR 26,81,083 from two parties. The break up of these deposits is depicted in the table titled ‘Deposits with AIDC concerning plastic parks (2015-16)’.

The AIDC website shows that most of the infrastructure in the project area is complete including the boundary wall, internal roads, drains, 10 MVA electrical substation and electrical distribution line. Three units have been allotted and 100 plots (various sizes), 10 industrial sheds and 2 warehouses are ready for allotment to the potential investors. The next section enquires into some possible reasons for changes in land area of the park.

Assembling Land for the Plastic Park

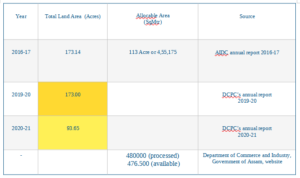

The land size of the Park was reduced to 93.65 acres in 2020-21 from 173.00 acres that was originally planned.

Reason for land reduction in DCPC records of Tinsukia park from 2019 to 2021 is unknown and provides scope for further exploration. Project costs etc. remain the same in DCPC reports for this period. The PlastIndia report for 2019 that mentions the area occupied by 14 plastic parks shows that the figure for Assam’s Tinsukia at 600 acres, is the highest among all parks. This figure differs from the DCPC records presented in the section above.

Land for the park was acquired in June 2010 but in June 2011 the Plastic Park had not been set up and instead the land on which it was to be built, came under the scanner of the CAG. In June 2010, the D.C. of Tinsukia acquired land from a Tea Estate in Gelapukkuri and handed over this land to the AIDC for setting up the plastic park. Part of this land was already mortgaged by the PNB Kolkata and the original title deeds of the land were in custody of PNB Guwahati. (4) The payment by the District Collector of INR 9.95 crore was irregular according to the CAG. The government replied in November 2011 that the district authority had no knowledge of the mortgage of land with PNB and so they paid the compensation without verifying the original title deeds (CAG, 2012, Page 13-14). No other information is available on what happened to this land for the plastic park afterwards. The case of Assam throws some light on the possible changes in land allocation of plastic parks.

What’s happening with Plastic Parks?

Much money, effort and land has been devoted to plastic parks projects since the inception of the scheme in 2013 but only a single functional unit at Tamot, Madhya Pradesh is producing plastic products. The Assam case shows how the valuation of the project cost varies and how the land area has reduced. It throws light on how the union and state government are financing the park where the number of functional units are still ‘under implementation’. The convergence of finance and land under the scheme for setting up plastic parks has not resulted in the production and export of much plastic. While this is a bane from the perspective of the plastics processing and exports, it could be a boon from the perspective of plastics pollution since capping the production of plastics articles is the only sustainable way forward.

1.These benefits include capital subsidy of 40%, reimbursement of ISO certification charges, reimbursement of patent charges, investment promotion assistance, exemption from stamp duty and registration fee, reimbursement of SGST on interstate sales touching upto 80%. These monetary incentives, tax benefits, reimbursements, discounts on power etc pertain to the size of unit in specific parks and are time bound for maximum 5, 7 or 12 years.

2. For four years, from 2007-08 until 2012-2011, long before the Plastic Parks Scheme was officially published on the Department of Chemicals and Petrochemicals (henceforth DCPC) website (26 June 2013), the Plexconcil, received grants from the DCPC for ‘plastic parks to promote cluster’. For two of the four grant years, in 2008-09 and 2009-10 the Plexconcil incurred an expenditure on plastic parks to promote cluster. It is likely that this involved advertising the Indian plastic parks abroad to attract investors as the expenditure is recorded as expenditure in Foreign currency (USD) on Plastic Parks to Promote Cluster (on payment basis). Out of the total grant from DCPC of Rs. 6,50,100 only Rs. 4,53,756 were spent. In relation to the other expenses of the Plexconcil however, the share of plastic parks was negligible. An analysis of the Plexconcil’s expenses on plastics parks and exhibitions (a major recurring expense head) and the total expenses from 2007 until 2020 demonstrates that the plastic parks occupy a relatively minor place in the Plexconcil’s overall agenda and expenditure.

3. Madhya Pradesh Park at Tamot is the only one to have received the third instalment of grant in aid from GOI.

4.The AIDC had paid the D.C., Tinsukia the estimated cost of the land—INR 19.10 crore and the D.C. paid INR 9.95 crore to the Tea Estate (against the total payable compensation of INR 17.36 crore). The balance compensation was not paid because of a writ petition filed in November 2010 according to which the concerned land was already mortgaged by the Tea Estate. The Tea Estate had outstanding dues and liabilities worth INR 4.46 crore up to 30 November 2009 for availing cash credit/overdraft/ loans/advances from PNB Kolkata against the mortgage of the land.

Centre for Financial Accountability is now on Telegram. Click here to join our Telegram channel and stay tuned to the latest updates and insights on the economy and finance.

Extremely interesting article. Thank you for it. While I cannot really fully take in the details, it seems that the production and distribution of plastics is lucrative for big business – and that the government is doing all it can to faciliate their easy functioning.

Along with all your other subheadings, I looked in vain for one titled, “Why ‘plastic parks’?”

How does the promotion of plastic parks (an oxymoron) relate to the purported phasing out of single use plastic?

Is plastic use set to increase in India, then?

Also, is there thought given to a circular plastic economy – is there any requirement for the industry to take back/recycle/think through the degradation of their product?

What about alternatives to plastics used in packaging – is the government also promoting those, or…?

What about the proliferation of plastic in consumer packaging – molded biscuit packing, individual wrappers, etc.? Are these parks fulfilling these “needs” as well?

So many questions!